Dear wanderer,

Disclaimer: the post contains explicit content: grotesque, violence, nudity, and various opinions on AI-generated visuals, ranging from cautious to neutral to positive.

All hope abandon, ye who enter in!

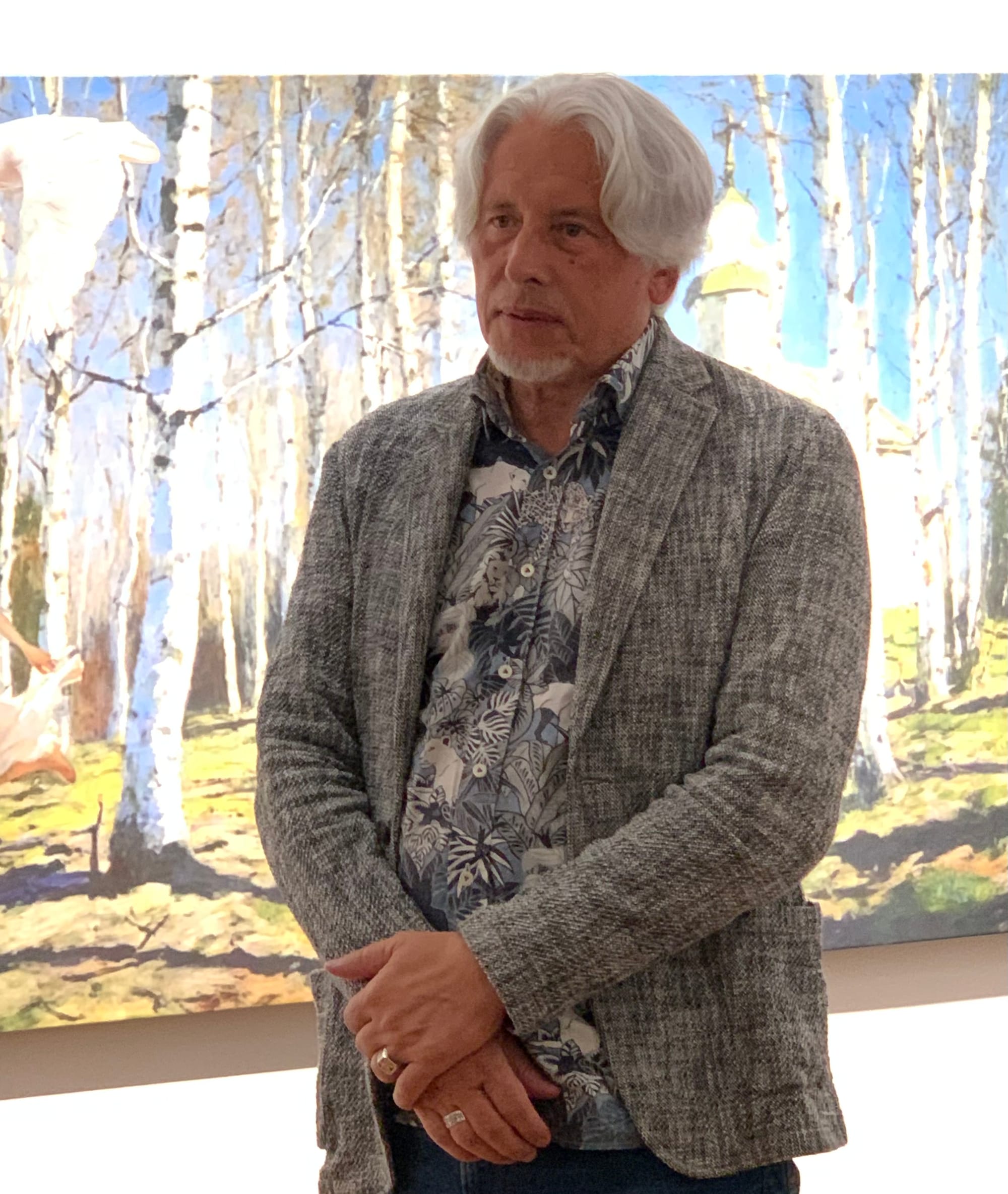

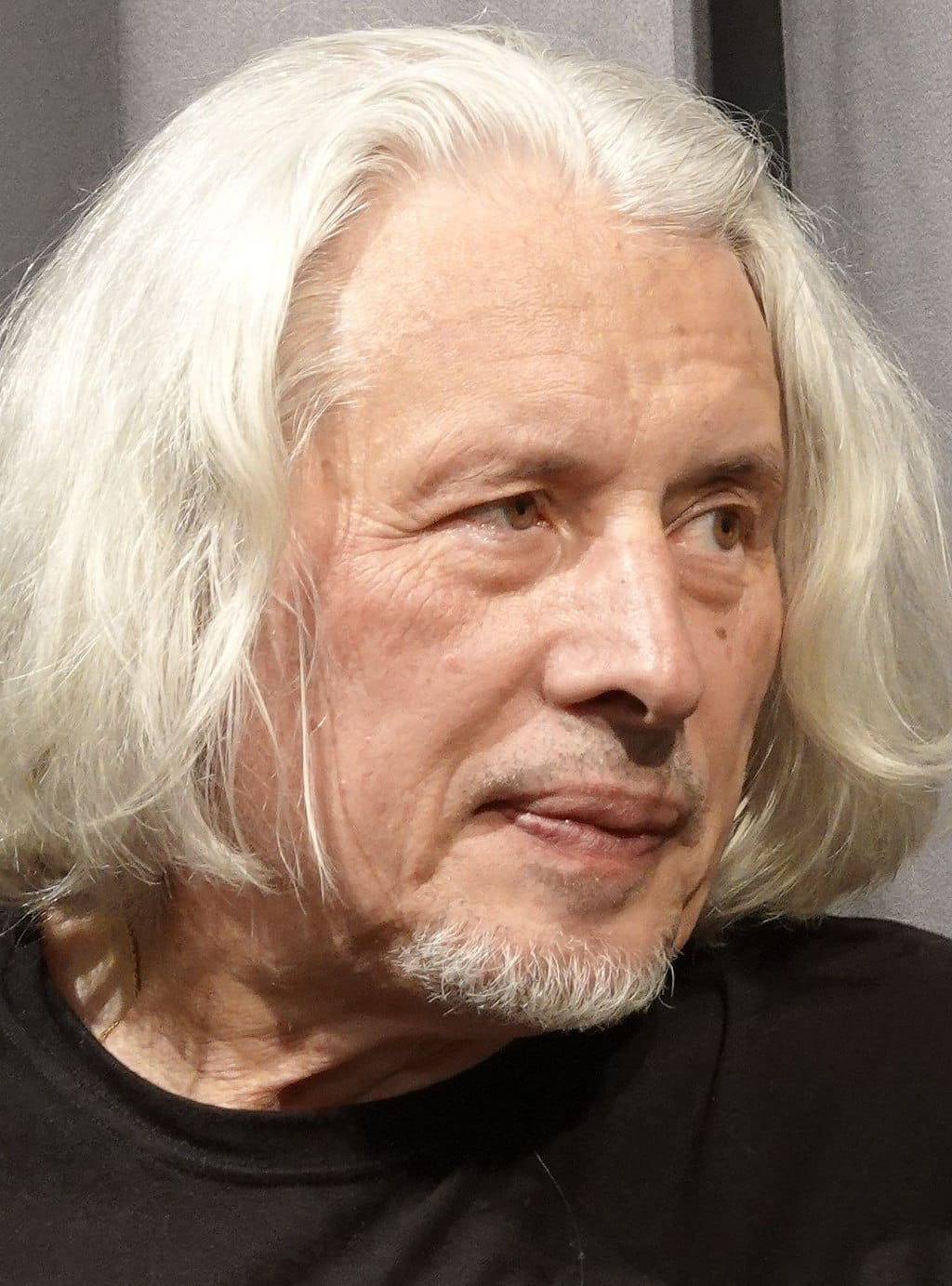

The most unforgettable experience of last week was seeing one of my favourite writers jumping into London's iconic black cab and zooming into the shop-surrounded and people-stuffed expanse of Regent Street. That happened right after I went to Vladimir Sorokin’s second exhibition featuring AI-assisted artworks based his cult book “Day of the Oprichnik”. As of the 30th of June, it is still on display in Shtager&Shch, a small gallery in London.

First, let me talk a little bit about the author himself to create some necessary context for those unfamiliar with his work and biography…

Vladimir Sorokin is one of the most popular and acclaimed contemporary Russian writers. His stories are provocative, surreal, absurd, grotesque, and transgressive, often portraying scenes that are taboo, disturbing, terrifying, and uncomfortable to read, yet often hilarious and always brilliant stylistically. Many of them are set in alternative or futuristic hyperbolised versions of Russia that blend elements of science fiction, satire, and social commentary. Now, he lives in Berlin, and many of his books are either restricted to distribute or completely banned in Russia, like his most recent novel “Legacy”. Over the years, even before the war, many of his books also caused a severe tumult among critics and outrage among the conservatives and pro-government activists.

Such as, in 2002, three years after the publication of Sorokin’s novel “Blue Lard”, which also was “the character” of his previous AI-assisted art project, the book caused a rabid controversy and a state scandal that led to the rapid growth in Sorokin’s popularity. The youth movement “Walking Together” held a police-protected demonstration near the Bolshoi Theatre, during which activists threw copies of “Blue Lard” into a huge styrofoam toilet. They accused Sorokin of distributing pornography and filed a legal complaint that led to a criminal case opened against Sorokin. For context, among many graphic scenes in the book, one of the chapters featured a quite explicit sexual intercourse between Stalin and Khruschev. The case, however, was closed "due to the absence of corpus delicti," as the examinations of the novel showed that "all explicit descriptions of sexual scenes and natural functions are conditioned by the logic of the narrative and have an undoubtedly artistic character."

“Sorokin's aesthetics neutralize all emotions, including sexual ones. This is the general principle of his work, without which we will never understand the innovative nature of this literature.”

— literary critic Alexander Genis about Sorokin’s work, in particular “Blue Lard”.

Literature in Russia still plays an important role in the society. During his readings and Q&A a few days before the London exhibition, Sorokin said: “Literature in Russia has always overshadowed philosophy and taken its place.” Even those who considered themselves philosophers often attempted to write novels to deliver and distribute their ideas (not always successfully). Russian writers are still looked at and listened to, they are celebrities, public thinkers, and their opinion at least arouses interest—people wait for an explanation of what’s going on, “who’s to blame” and “what’s to be done”, at least in a metaphorical way. The government seem to understand it and sees potential danger and a literal threat in the literary word, thus, at it has been for ages, writers in Russia have been subjected to controversy, censorship, prosecution, oppression, banished, hounded, imprisoned, and killed. The whole culture, as it seems to me, was formed not “thanks to”, but “in spite of” the state, and it remains so. The state didn't foster culture; the culture, the one that’s remembered, thrived in resistance to it. Thus what Russia really is, or was or will be, can often be seen in literature more than in philosophy or sometimes even history.

“Day of the Oprichnik”, Sorokin’s novella, the main subject of the aforementioned AI exhibition, is one of such books. It has become a cult classic and now considered prophetic because all of the grotesque in the book has emerged into reality after the publication. Having been asked how he managed to predict the future, Sorokin only said that he doesn’t know, it just happened, and, perhaps, writers “have a special antenna for that”. Despite all the buffoonery and absurd events happening in the book, the similarity to the present reality is uncanny and ofttimes depressing and horrifying.

So whether to go and see Sorokin presenting a project that combines the author’s vision with modern technology based on an excruciatingly topical book was a straightforward decision, as well as was the decision to share the experience with my readers.

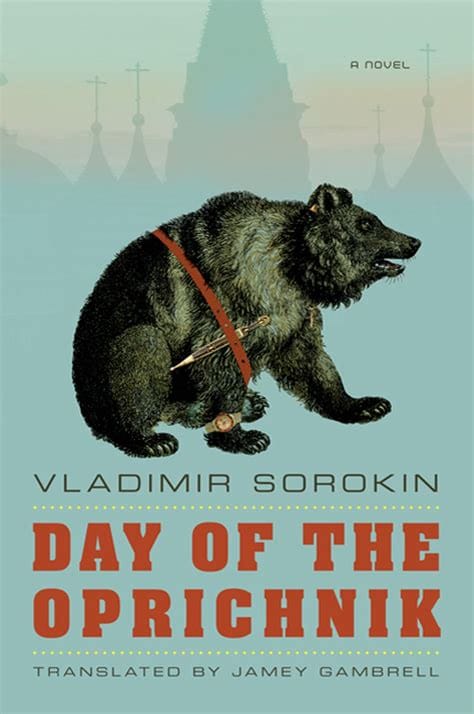

Various international editions of "Day of the Optichnik"

The story takes place in 2028, when Russia has gone through Red Turmoil, White Turmoil, Grey Turmoil, experienced the Rebirth of Rus, and now is isolated from the rest of the world by the Great Russian Wall. It has the Sovereign, flourishing xenophobia, protectionism, cheap patriotism, and the omnipotence of corrupted punitive organs to carry out constant repressions. Supermarkets have been eliminated, replaced by kiosks offering two variants of each product. The sources of income are natural gas sales and fees from the transit of Chinese goods to Europe. Luxury items, cars, and airplanes are all Chinese, with twenty-eight million Chinese living in Siberia.

But the focus of the story is on the restored Oprichnina. Russian Tsar Ivan IV, also known as the Terrible, created it in 1565. “Oprichniki” was his own personal guard and thug squad who went around terrorizing nobles, grabbing their land, and generally making life miserable for anyone who looked at Ivan funny—all to strengthen the Tsar’s autocratic rule.

In the story, we follow the story of an ordinary day in his life of Andrei Danilovich Komyaga, one of the oprichniks. He lives surrounded by servants in a terem (wooden palace) confiscated from an enemy of the people. He travels to work on a lane reserved for oprichniks in a "merin" (Mercedes) with a broom and a dog's head tied to the bumper (a symbol of the real oprichniks). At the beginning of the workday, he is to execute punishment on a nobleman. He and his crew kill the disgraced person, burn his house with flamethrowers, and rape his wife. After this, the oprichniks go behind the walls of the white-stone Kremlin (it was white before) for the absolution of sins at a service in the Assumption Cathedral. By the end of the day, Komyaga is to meet with a clairvoyant, the dissolute Sovereign's wife, experience a drug trip, and participate in a gay orgy with his comrades in a bathhouse, strengthening the unity of the oprichnik corporation.

Both Vladimir Sorokin and Marat Guelman, the exhibition’s curator, described it as an art project or an art installation rather than a series of paintings, which is a fair way to position it. For Sorokin, it was a chance to see his book coming to life, even though the images were always not as he imagined them in his head almost 20 years ago. He said they are not book illustrations and shouldn’t be considered as a part of the story, but a separate project “inspired by” it. Artworks included scenes that were not in the book but could still take place in the world depicted in the story, exploring its extra facets.

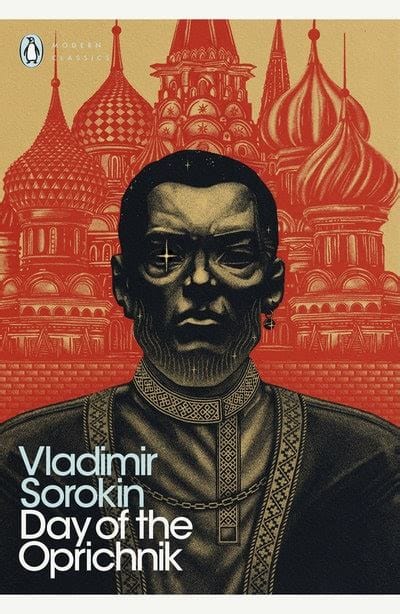

Sorokin isn’t only a writer but a painter. He began his artistic career in the 1970s among Moscow conceptualists and worked as a book illustrator, but, after many years focusing on literature, returned to visual arts in 2013 after feeling creatively drained from writing his novel "Telluria". In 2017, in Tallinn, Estonia, his exhibition "Three Friends"showcased 19 canvases and 7 graphic works, each deliberately executed in different styles.

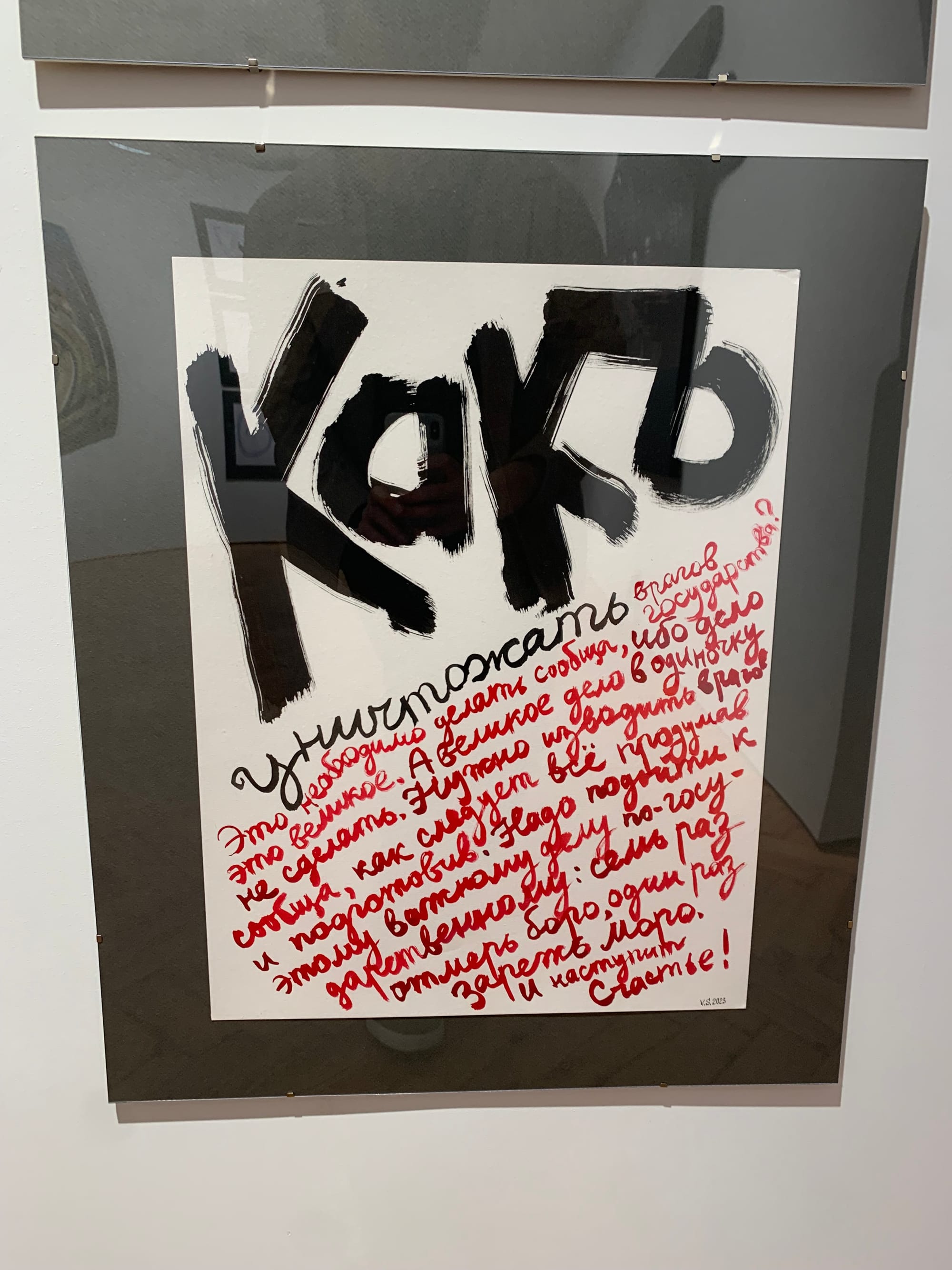

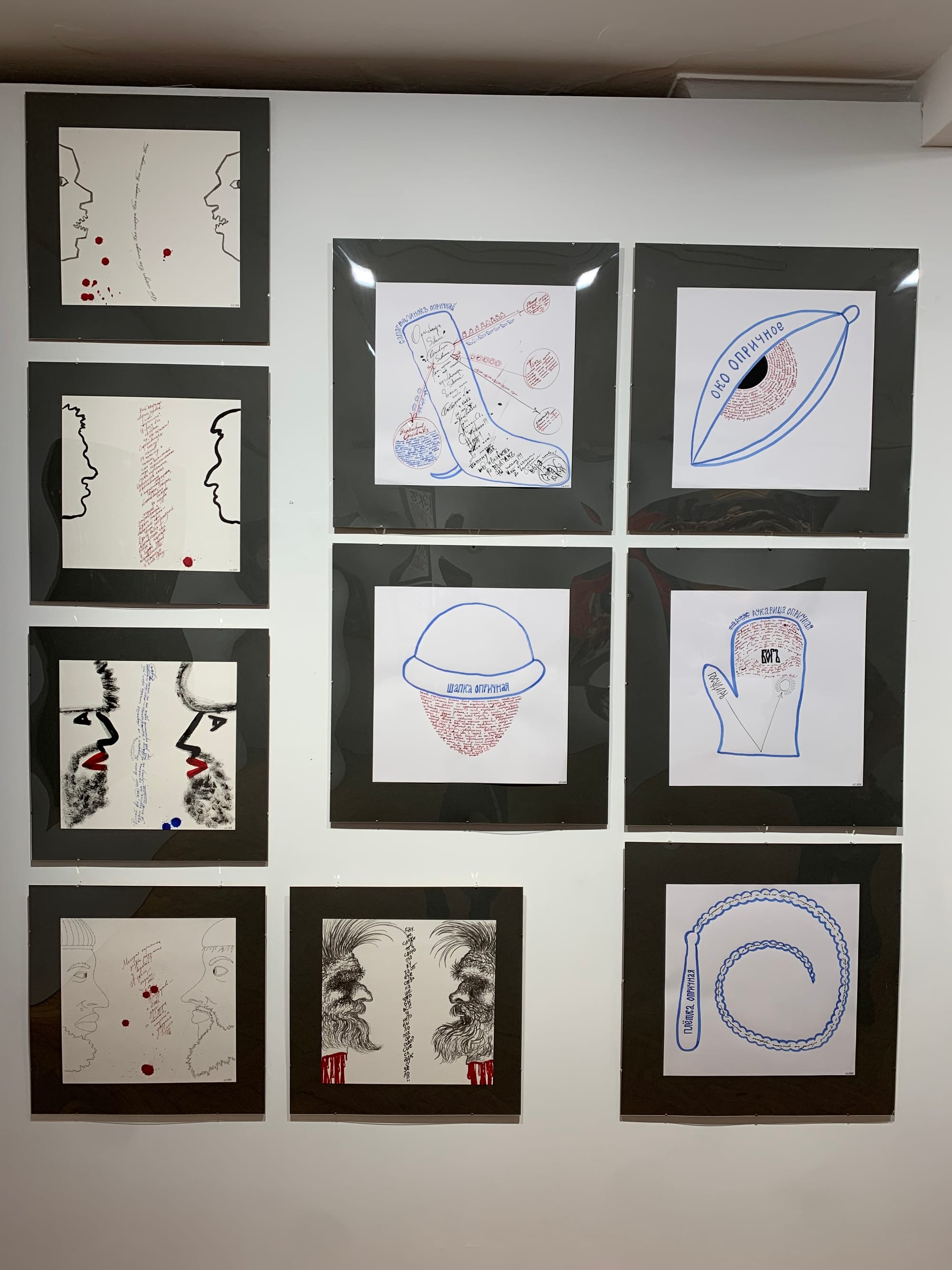

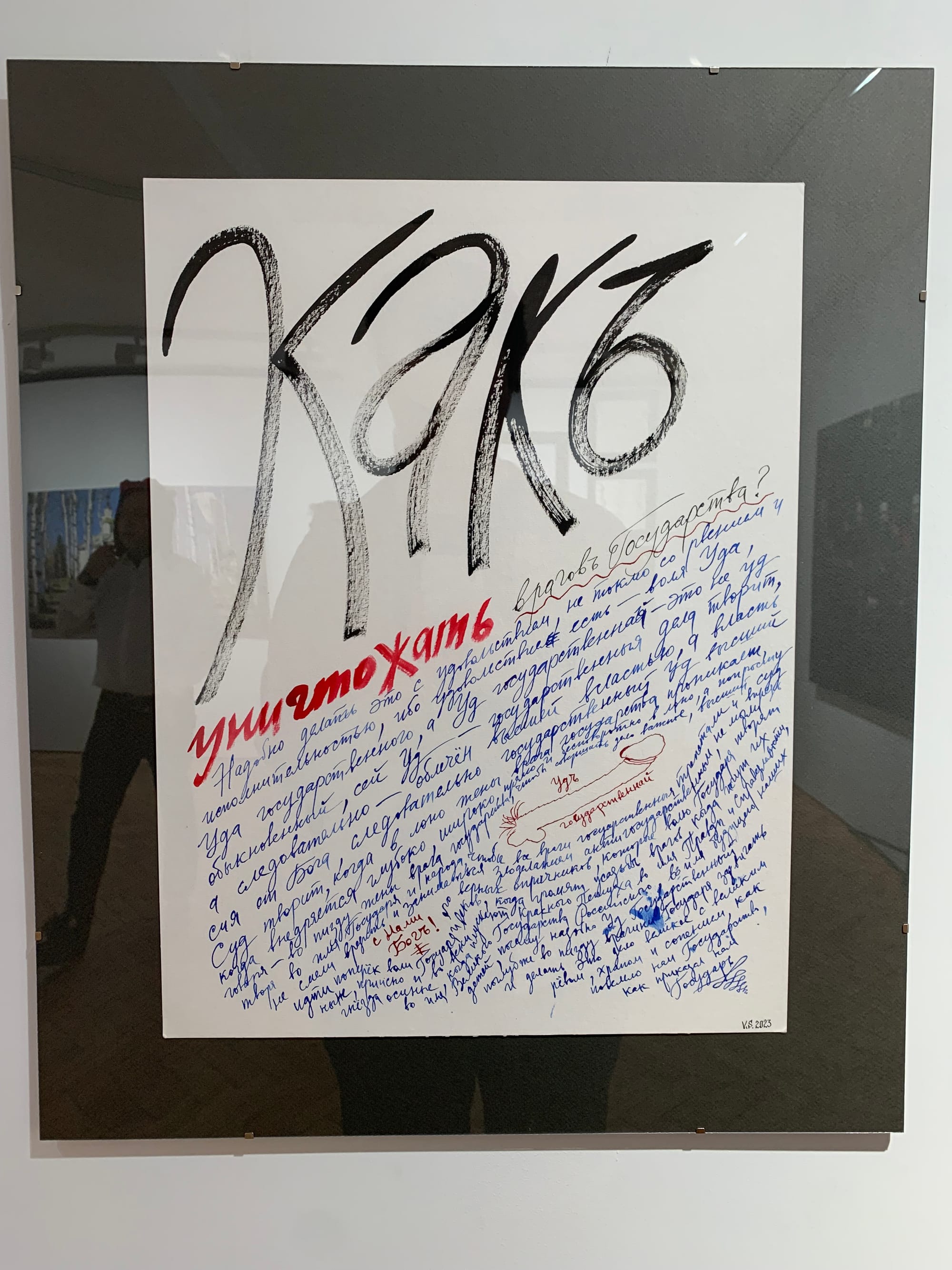

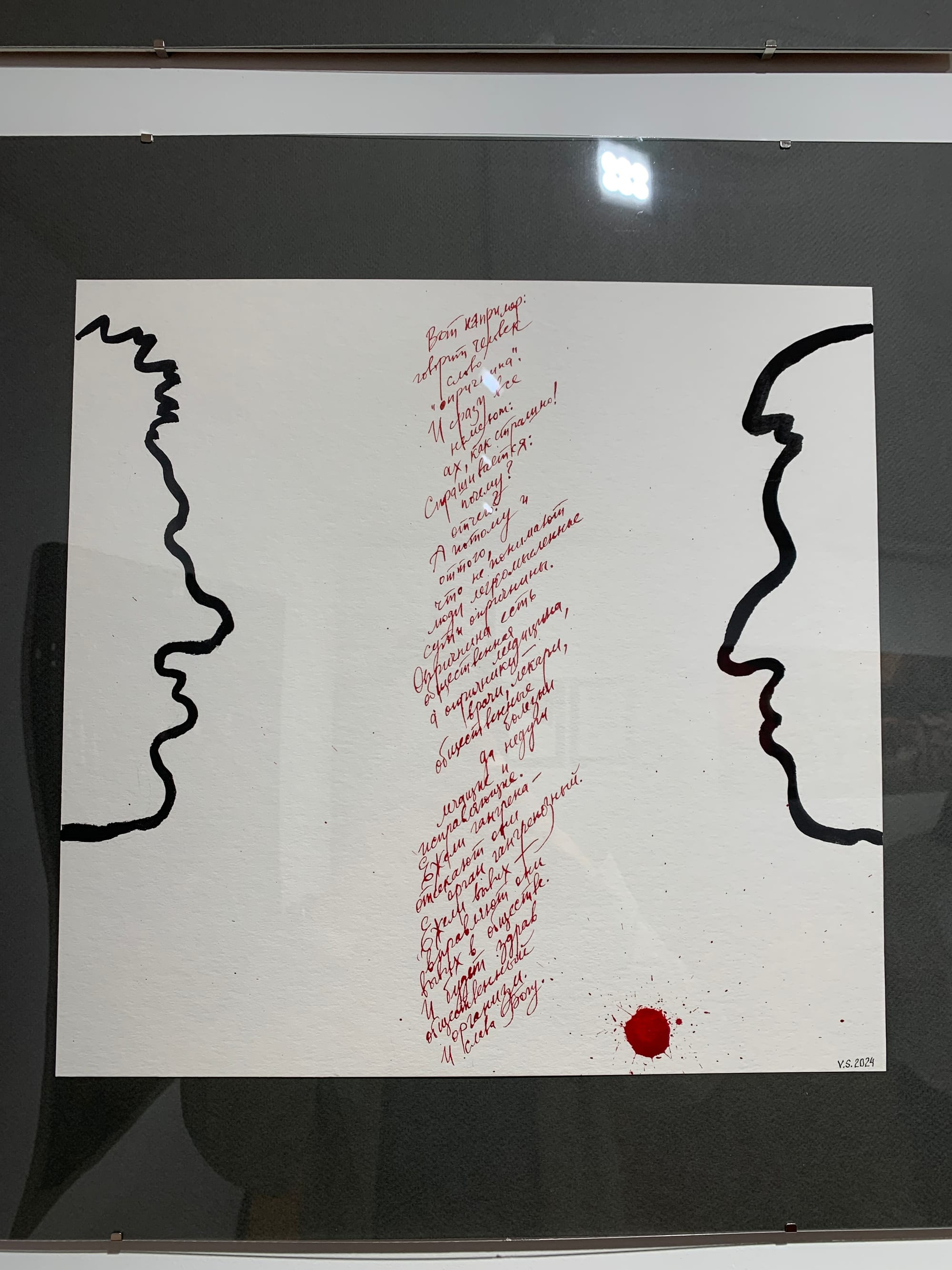

For “Day of the Oprichnik”, he also created several graphic works himself, each of them featuring a differently lettered passages from the book alongside with deliberately minimalistic drawings of intrinsic elements of the Oprichnina, such as an oprichnik glove, oprichnik hat and so on.

Sorokin's graphics for "Day of the Oprichnik".

“Look, these are made by AI, and these are made by human,” he said, subtly hinting that the idea of juxtaposing his simple hand-made graphics with intricate AI-assisted artworks was to emphasise the contrast and fundamental distinction between two ways of artistic expression. In one of his interviews in the past, he described traditional, analogue painting as a dance-like performance:

The canvas demands a ritual dance from the artist. You prance around with brushes, palette knife, and palette, step back, look, then run up, wave a brush, mumble something. Hands covered in paint, sweat streaming, feet getting tired. When you're painting, you completely forget yourself. It's wonderful! It really refreshes the blood.

Working with AI was something completely different, not only because it was done on a computer. One piece took Sorokin many iterations, experimentations and tweaks, and approximately two weeks to finish. And he finished the whole project in one year. He recalled his awe at the technology, yet mentioned the loss of full control over the work. Thus, the first painting below required a great effort to describe the scene to achieve the desirable result, but everything changed dramatically after adding one word to the prompt—”night”. The AI didn’t just change the time of day, but added a puddle with the moon’s reflection, the dark fir trees in the background, and deepened the perspective, while preserving the key elements and characters: the woman, the white raven, the priest, the oprichnik, and the church.

Two pieces imagining the same scene during the day and at night. The oprichnik riding a priest chases a young woman in the forest.

During the process, Sorokin acted more like a director giving instructions until the desirable result is reached rather than an artist, the difference he could see clearly being an experienced artist himself. Given at the present state of generative models full control can’t be achieved, there appears a distance between the author and his creation, and the author from one who creates something from nothing becomes closer to an observer, who, like the audience would, witnesses the performance unfolding before him, gives directions, and says “stop'“ when satisfied. It is, in a way, could be seen as a weird type of photography in digital space, where you go to a specific place (ask to create it), choose a spot, an angle, any other relevant conditions, and wait until the latent space (the artificial nature) assumes a shape you find satisfying, while you still can’t change everything to your liking (unless you photoshop it, of course).

One of the most striking moment of the exhibition was Vladimir Sorokin’s acomparison of AI with an infant mentioned in Andrei Tarkovsky’s “Solaris”. It wasn’t in the book and it’s assumed that Tarkovsky added the infant to his film as a part of his reaction to Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey”, which he described as “phony on many points, even for specialists; for a true work of art, the fake must be eliminated.” It’s even supposed that “Solaris” was made to outdo Kubrick. The infant then is probably a deliberate subversion of the image from the Odyssey’s ending, and yet I feel that both versions of it, Kubrick’s and Tarkovsky’s, are relevant to the reference Sorokin made.

In “Solaris”, the pilot Berton describes a giant newborn child with blue eyes that he saw on the surface of the Solaris ocean:

"It was a child," young Berton answered the scientists.

"What child?" Shannon asked gently. "Had you seen him before?"

"No, never. At least, I don't remember it. As soon as I got closer (I was about forty meters away from him - maybe a bit more), I noticed something wrong about him."

"In what sense?" Chris couldn't hold back.

Old Berton remained silent.

"At first, I didn't know what it was," young Berton said quietly, "only a little later I realized that he was unusually large, gigantic. That's still an understatement. He was probably about four meters tall. When I hit a wave, his face was slightly higher than mine, even though I was sitting in the cabin, that is, I was three meters above the ocean surface."

"If he was so big," said Chris, "why did you decide it was a child?"

"Because," replied old Berton, "it was a very small child."

"That's illogical," said Chris.

"I saw his face, Chris."

"He seemed to me like a complete infant," Berton continued on the screen. "He was probably about two or three years old. He had black hair and blue eyes... enormous," Berton nervously crumpled the notebook pages with his fingers. Then he raised his hand to his throat and abruptly unfastened his collar, so that a button flew off.

"Are you unwell?" Shannon asked. "In that case, we'll postpone the commission meeting."

"No," said Berton. "I'll continue... He was naked, completely naked, like a newborn. And wet, or rather, slippery. His skin was shining. This sight had a terrible effect on me. I saw him too clearly. He was rising and falling with the waves, but independently of this, he was also moving. It was disgusting," Berton said this, shuddering.

Old Berton abruptly stood up and turned off the device. For some time, all three were silent.

"He was opening and closing his mouth and making various movements. Disgusting! These weren't his movements..." the old man finally said with revulsion.

"What do you mean?" Chris asked.

"As if someone was studying him."

"I don't quite understand..."

"I don't know if I can explain... I had the impression... His movements were unnatural..."

"Do you mean his arms were moving in ways that human arms can't move due to joint mobility limitations?" Chris asked.

"No, not at all. But his movements had no meaning. Every movement, in general, means something."

"But an infant's movements shouldn't mean anything."

"An infant's movements are chaotic," said Berton, "but these were... they were methodical... They were performed in turn, in groups and series... As if someone wanted to find out what this child could do with his hands, and what with his torso and mouth. The worst was with the face... It was, perhaps... It was alive, but not human... Anyway, let's watch further... There's a lot of unpleasant stuff here, we'll skip it."

Later in the film, the reason for this child's appearance is explained: in a telephone conversation, Berton remembers that shortly before his spaceflight, he saw a very similar newborn while visiting someone. Consequently, the sentient ocean Solaris “extracted” this memory from his mind and materialised it in a distorted, frightening form, creating something both familiar and deeply alien, something of us and other than us, without having an understanding of what it is and how it should be.

Sorokin seems to suggest that artificial intelligence, like the infant in "Solaris", is a manifestation of human knowledge, desires and memories. It exists in a liminal space between reality and imagination, potential and actualisation. It's something that is created from our collective knowledge, yet it exists in a realm that's not quite fully real or understood, much like the mysterious phenomena on Solaris that attempted to imitate a human without, as Berton said, “meaning”. It’s also quite interesting to look at the same problem via the same image in Kubrick’s “2001”, where it potentially symbolises the next stage of human evolution: from an ape to a man to the celestial Starchild.

The question I asked myself during and after the exhibition was, would I go to a similar event if it wasn’t by Sorokin or some other already famous author or artist I admire? Unlikely, nay it depends. In the art history, more so in the most recent centuries, an artist’s name and the vision behind the work has often been meaning more than the work itself. I have a similar sentiment around “Day of the Oprichnik”.

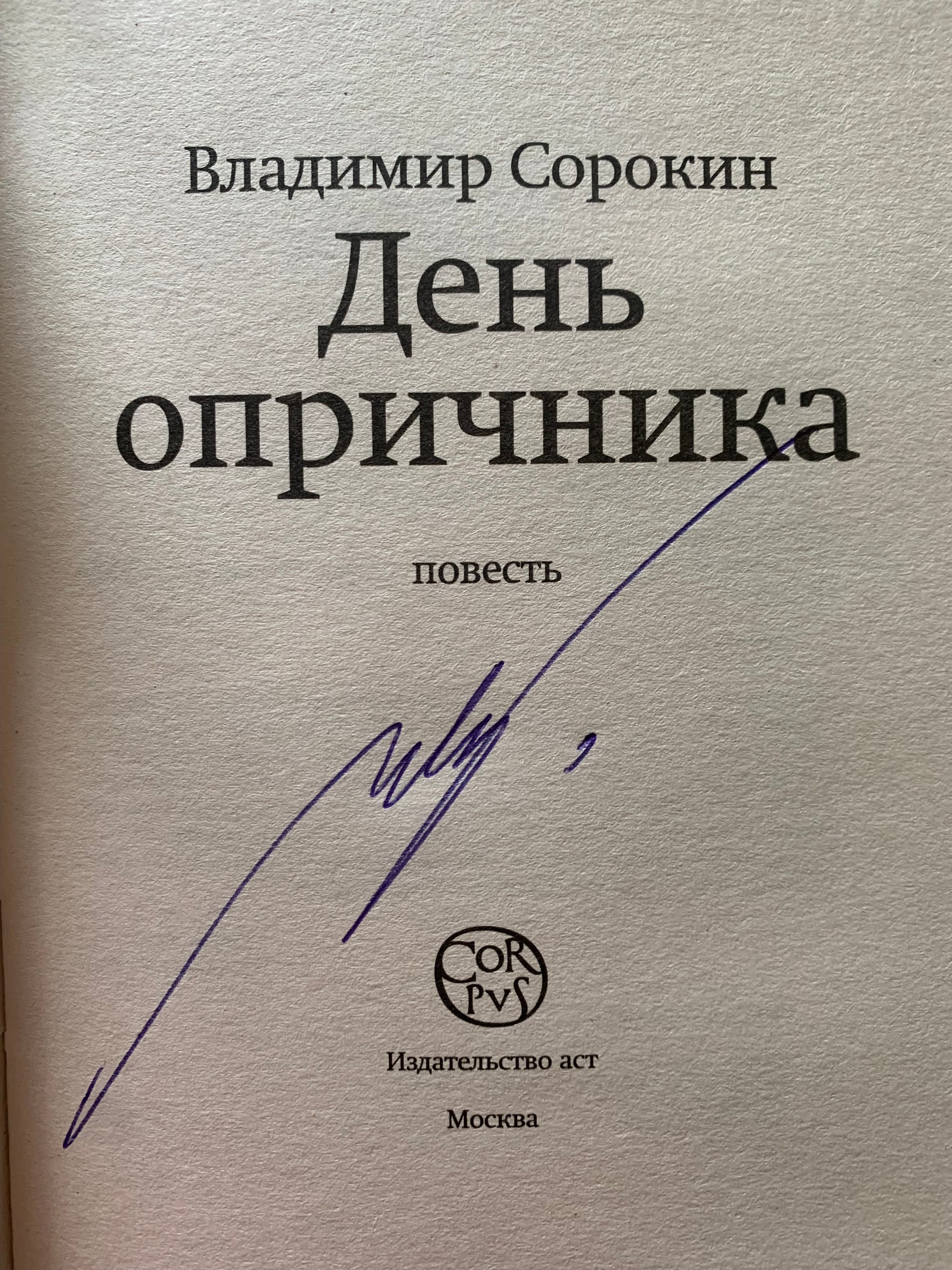

I loved the novella, had a copy of it signed by the author in the past week as well, and I was excited to see the experiment Vladimir Sorokin prepared, and genuinely enjoyed it. He is the most bold and fearless writer I know and in many ways he has been a role model for me since the first story of his I read. He showed me with his keen mastery of style and shocking sharpness of image how one can do literature—after all, if he can put in his book something that you wouldn’t dare to discuss with your friends and family, why can’t I write about whatever and however I want? So it was important and inspiring for me to see him in real life and to hear his opinion that clearly stood aside from the typical internet discourse on the topic. I was glad to see that someone like him, an accomplished author who has started back in the 80s with a dissident novel published through samizdat, an actual artist, a painter working in a physical medium and having exhibitions, not to shy away from the modern technology and use it as a new type of expression and give his stories another life.