Airports smell of time in the same manner as the smoke from smouldering sawdust, bittersweet. The waiting room for the Myrvínka-Strötzwen flight is well ventilated, unlike my head. Still steeped in moonshine, my thoughts, puffing at each other with hangovers, are on a philosophical rave.

—Drink, son. You're a man, aren't you?

Reddened faces with burst capillaries around me chant "drink!" bumping their fists on the table, bottles shaking, shots clinking. Dishes aplenty huddle together, leaving not a centimetre of space: boiled and butter-drenched potatoes with dill, infernally smoked perch in illegal quantities, pickled vegetables drowning in brine, fresh vegetables drowning in mayonnaise, a fly drowning in mayonnaise, too. Drops of mayonnaise fly from my niece's plate onto my red cashmere jumper (I have no idea how to wash it) as she slaps her spoon on the soup's surface, covered with mayonnaise. A two-litre bottle of moonshine with a cork left in its neck is proud of its totalitarian reign over the table. Dad uses corks to seal his moonshine bottles. He fancies himself an artisanal distiller and, to his luck, is friends with the coppers.

—Drink! Drink! Drink!

—I'm not drinking that, it smells terrifying.

—"Terr-rr-ific" you wanted your say. Drink!

Welcome, dear regret, I haven't had enough of you. “Drink!” I know we'll finish the bottle and commence a swimming contest in the river Golva, cold in temperature, clayey in colour, and cunning in current, covered with layers of lemna and poplar fluff. My relatives' favourite lemma: everything's better with mayonnaise. "Clouds" is when you lay mayonnaise over a shot of moonshine. My dad's atemporally temperamental, he loves swimming, loves it so much, so he has always wanted to teach me how to

—Just fuckin' swim already!

—*tortured murloc sounds*… I can't… *grgl* I think I'm drowning.

Water gurgles in my throat, echoing through the skull bone.

—You what, aye?

—Drownnmnlnming.

—Don't you worry lad, I'll tell you when you are!

Delays, queues, security checks, more queues, people sleeping on the ceiling, my luggage lost with my nurofen, sour grimaces, coffee and croissants costing like a jet's wing, timeless, untameable roads of travelators and escalators are all trifles — the waiting time is the real enemy. You wanted to save time on a train journey, but now look at you, wasting time. But how can you waste time? The whole point of time is to be unremittingly wasted.

—I think it flows in multiple directions at once.

—What, Golva?

My dad, my auntie, and my sleepy uncle peek deep into my eyes, their fingers ready to dial the number of the mental asylum, while my sister with her daughter giggle beside them.

—No, the time!

—Bollocks!

—Indeed it is! Let my lad speak.

—Imagine. Simultaneously you experience the past, the present, and the future, and not only experience but change them. You're here, in the infinitesimal present, sandwiched between two strata of time — the past and the future. The memories, they shape you, and you, in return, review and reshape them, until there's nothing left of what really happened, and instead only what the present you have created for yourself — the time never been.

Dad's moonshine tastes like a kitten has pissed into a basket of strawberries.

—Same with the future. You plan, scheme, ponder, become excited, hopeful, anxious, all that, experience some sort of eschatological dread even. So you live in all three times simultaneously while not being in any of them! *hiccups*

—Huh?

—What's that "huh"?

—I can't make head nor tail of what you're gabbin' on about, son. I'm not a fuckin' dictionary, am I?

—Uh-huh... No, I suppose.

—But I've always reckoned you were a smart lad.

How painful it is to return to the homeland, that home, that street, after so many years of being away. One who is not who he was comes to a place that is not what it was, and two entities, the character and the place, meet each other again, as if for the first time, with a hint of déjà vu (sometimes toxic), two either idealised or despised images sprouted from the imperfection of memory. It's never a full circle. It cannot be. One never comes back to the same point. One doesn't have to disguise oneself as a beggar or someone else, for one is already disguised.

—I want a grandchild, son.

—What for?

Once upon a time, my dad's archnemesis from the flat next door spread rumour that he, my dad, eats them, infants.

—Your little lad, when you bring me your little lad?

—I don't have any, Dad.

—Look at us! I and you — Olympians! I've passed you bloody good little helix things, you know. They say you don't waste good genetic material. Precious these days with all those aborted degenerates running around.

—Dad...

—What is your wife doing?

—I don't have a wife, Dad, I told you I don't have a wife.

—That's a shame. I thought you lied to me, though. I've always reckoned you were a good-looking lad and a bit of a wily bastard. Don't lasses like you?

He frowns and squints, his bushy eyebrows spread like an albino peacock's tail, and with an expression of the ex-secret service officer, who he perhaps was, he bends towards me and whispers:

—Do you have a husband then?

—I don't have a husband either, Dad.

He sits back, throwing up his hands in disappointment.

—Do you have friends, at least?

—I do have friends, yes.

—Have pity, son. I'm old, you know. Might not see your little duckling running around the house.

Mallards occupy leaf-ridden Golva's ocean ("Green-headed bastards!") and swim in uneven spirals, quacking, feasting on food provided by the audience or on lemna if the audience is absent. A baguette half my height warms my cat-scratched palm, warms my nostrils scratched from sniffing snot, and warms my brain scratched by an unsuccessful chess class. The pawn is my dad's favourite piece ("One has to learn some compassion for 'em peasants."). I nibble on the baguette, break off a piece, and throw it to Golva. Circles of startled water scurry away from a bready pebble, quaquaversally, in the same fashion time does from a person. Mad quacking shakes the surrounding space of the river's quay, and the ducks pounce on a piece of bread, scattering fallen leaves aside. A flock of pigeons, who have been pleading with me for food, are horrified and blown apart all over the quay. My cheeks are flashing and melting from joy, snot is dripping from my nose. I demonstrate my braces to "the green-headed bastards", stuff my mouth with warm baguette, share another scrap with them, and in a second, dad smacks me on the back of my head.

— Who feeds 'em birds with bread, eh? They'll be as good as gone, green-headed bastards. And put your hat on, won't you?

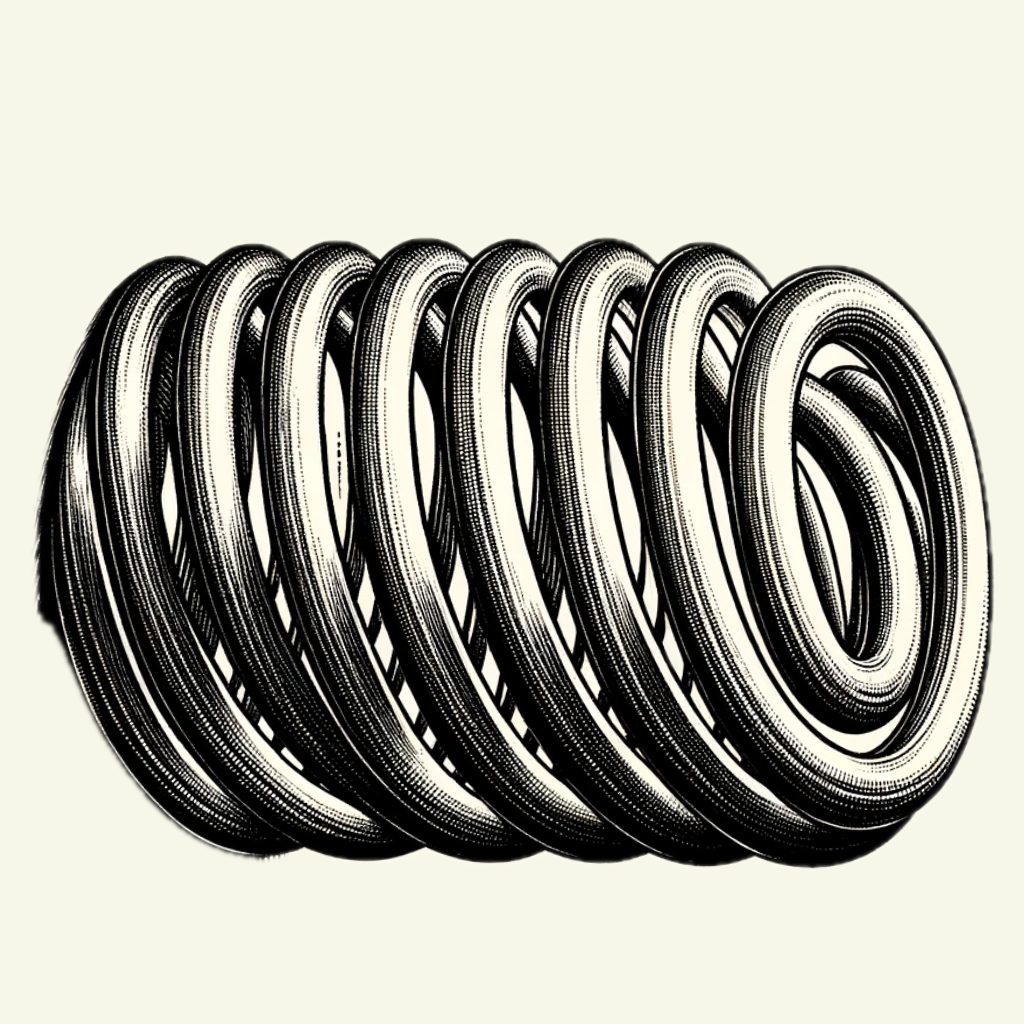

It is going outwards from the centre. It is a spiral, a spring that someone once squeezed and released. It is a spiralling staircase that you climb, and climbing only becomes harder and harder. Time is a helix. Everything is a helix if you look at it from the right dimension. The duck's penis is a helix, too. Male ducks have corkscrew-shaped penises, and forced copulation is common among ducks. In response, female ducks have evolved complex vaginal structures, including spiralling and labyrinthine vaginas, to prevent full insertion of the male's penis and control fertilisation. This co-evolution, where each sex evolves reproductive traits to outcompete the other in the battle for reproductive control, is described as an escalating sexual arms race in ducks.

—They're gunna bomb us, son.

—They're not gonna bomb you, dad.

—Aye, they will. I feel it in my bones. We're losing that bloody arms race.

—You've been saying that for as long as I can remember.

Like on a trampoline, I'm bouncing on our old sofa trimmed in what's now called vegan leather, listening to how the rusty springs are creaking in agony under the pressure of my weight and how my dad's swearing at the telly in the next room. Someone is bombing someone, a common state of affairs nowadays.

—Unbelievable! Unbe-bloody-lievable. They are actually doing it!

My brain cells at this age are still in a mode of looking for meaningful connections with each other, so I continue bouncing and each of my landings resonates through the whole room, the floorboards creak, the windows shake, dangles the chandelier, and rings the crystal set behind the glass doors of the cupboard. There, in the dark, covertly ferments my dad's blackcurrant tincture, artisanally produced. It's a tightly corked five-litre jar, looking like a barrel with a narrow neck. The vibrations from the sofa creep towards the bottle, disturbing the peace of its cushy chamber, envelop the bottle and call the pressure to come out, and the pressure, in turn, being quite claustrophobic, acquires a strong desire to see the light, yet cannot — the cork does not allow that. Then, the pressure, pissed with the state of affairs, decides to exit sideways, quaquaversally. All I hear is an explosion, a rapid expansion in volume of a given amount of matter associated with an extreme outward release of energy and compressed gases from inside the blackcurrant tincture bottle. Shatters the crystal set, shatters the glass door; shake the windows and chandelier. The door of the cupboard blasts open, and from there, riverly, the black-red mass spills over the old carpet, flowing between the floorboards, silencing their creaks, and under the sofa, surrounding me, leaving no escape route. The floor is lava now.

—Bombing! They're fuckin' bombing us!

My dad rushes into the room, ducking down, glaring around, at me, at his favourite black-red liquid that pools over his favourite carpet, at the cupboard filled with pieces of his favourite crystal. I already know he's angry, and I already know what's coming next.

—Sit tight. Get your thighs

Ready for your old soldier's belt buckle, I know, I know.

Buckle up! Our lowcoster plane finally reestablishes contact with terra firma in the airport of Myrvínka, after not more than a half an hour of spiralling over the city like a leaf chastised by gravity. A round of applause for the pilot, of course. Thanks for not killing us! The gods are pissing freezing rain over our heads protected with duty-free bags. Everyone escapes from the plane to the terminal, sloshing through puddles and splashing dirty rainwater all over each other. I hand my passport over to a woman wearing a uniform and no expression on her face. My red cashmere jumper has no stains of mayonnaise on it yet. Thanks to my coat, it's not soaked either.

—Purpose of your visit?

—Seeing family.

She detectively examines stamps in my passport.

—Where've you been for eleven years?

—Erm... Studying and working.

I see something surfacing on her retinas.

—Why are you coming back?

On the retinas, I read a fresh inscription that I'm not welcome, and a thought that has been fermenting in the back of my mind cupboard for years now enters the labyrinthine structure of my brain like a corkscrew. What if the city, on some subtle energetic level, refuses to accept me and rejects me like a transplanted organ? What if during one of the walks along the famous Myrvínkian wide avenues guarded on both sides by tall poplars, which in June carpet everything around with fluff as if with snow and in October with leaves, or along narrow streets among old shrivelled wooden houses, mothballed under eternal restoration, as if that is what they are condemned for by time, or on the high hills, from which the whole city with its brown tiled roofs could be seen, sunken in the sea of trees, and the river Golva, which zigzaggedly pierces Myrvínka through, shallow but still deep enough to take a boat or to swim, I would feel myself a stranger and an abyssopelagic dread would squeeze me into a molecule under its pressure. What if I meet one of my old friends with whom I have long since lost contact, and, even out of common courtesy, have no choice but to respond to this

—Hi! Is it really you?

Who? Me? Even I don't know that.

—It is, apparently, yeah. Nice to meet you. Erm, again.

—You're looking good!

Not the best I can manage.

—You're too. Looking good, I mean.

—How many years? Ten, fifteen?

—Eleven, actually.

—Ah, yes! Since the school, what a time, right-right.

—Yeah, what a time. Flowing weirdly, that thing.

—Oh yes, indeed. How have you been all those years?

Oh, splendid. Job, and well… job.

—I'm good, alright, not too bad, coping.

—Do you have kids?

This is everyone's favourite question. I wonder why the border control lady didn't ask it from me.

—I have a niece, yes. She's cute. Look at these stains.

—You look like a mushroom!

—I know, right, she's an artist.

I would wager she's in cahoots with the demons, even though she has an angelic face. She looks, no — stares at me, like at an unknown species. I'm an uncle, a wise adult man who shares some of my dad's outstanding genetic material. Hither and yon, I shall act as an adult and teach her the arcane knowledge of how to separate a head and a tail and bones and eat the river fish properly.

—I don't like fish.

—Well, that's a shame. Fish have plenty of useful things, for example, omega-3 for brain development.

—Has the fish helped you at all?

Down the winding staircase, I descend and emerge into the airport's hall, a monument to brutalism. In front of me, right above the airport exit, a plain cement bas-relief with the Myrvínka coat of arms features a mallard sitting in front of a poplar. I reckon that's why we're screwed from birth. There's nothing to see in the city. It's nothing like Babylon, with no skyscrapers, no hanging gardens, no temples, nor epics written on ancient tablets, and everyone speaks the same language. Entering the city, I feel I'm provided with free shackles and here and now my life is over, so all I have left to do is to ferment my memories in small bottles until they explode one day. There are no foreigners, no tourists, no strangers, except me now — the squares and streets are empty, shopkeepers sleep in their undisturbed dens. People stroll through the streets, tapping their canes on the pavement. Nobody smiles at you, except when they think you're a clown in your red cashmere jumper. Cars breathe at you with eye-scorching fumes and, growling, fly past you splashing mud from non-drainable puddles, an irreplacable part of the city's landscape design. Black cats wait for you to cross the road. Pigeons swear at you behind your back. Squirrels... well, I don't know what they do, they are just on the trees somewhere. Yet, there is something peaceful, soothing to the soul both in the silence and in the constant quaking of ducks, something lovingly engulfing you whole in its bog.

—Oi! Stand where you are! Don't move!

My feet are drowning in a spring field. The snow has melted, and it's turned into a brown swamp ready to suck me into the abyss and pressurise me. My body is already up to my waist in filthy viscous goo and the soil keeps engulfing me.

—I can't move!

Dad rushes towards me, shuffling his feet in knee-high rubber boots that are also bogged down in mud. I don't fear being buried in soil, for I don't have that emotion yet, or perhaps I already know that's what happens to all of us asymptotically, to grandpas and grandmas and mom, but I see a horror in his eyes as he's approaching me and I become scared too, scared that he's scared, for I've never seen that in him, not because of me.

—Bloody hell, why did you go in there, tell me.

He wraps his heavy arms around me and pulls me out of the mud.

—Thank you.

Says I and hands over the cash to the taxi driver who takes the banknotes and, not looking back at me, nods stoically in response to my gratitude. The car rockets off down the avenue, a tunnel of poplars, leaving a cloud of smoke and quaking drone in its wake. I stand in front of our old shabby stone house with my backpack and suitcase, darting glances at the neighbour's windows, yet nobody hides behind white, patterned curtains. What if we won't find common ground with him, and he will never want to see me again? What if he would rather not see me already? I gently push a familiar doorbell button and wait until behind the door I hear his rasp and low voice.

—If it's one of you brain donors and your pyramid schemes again, I swear I'll cut your bloody fingers off and screw ‘em up your arse.