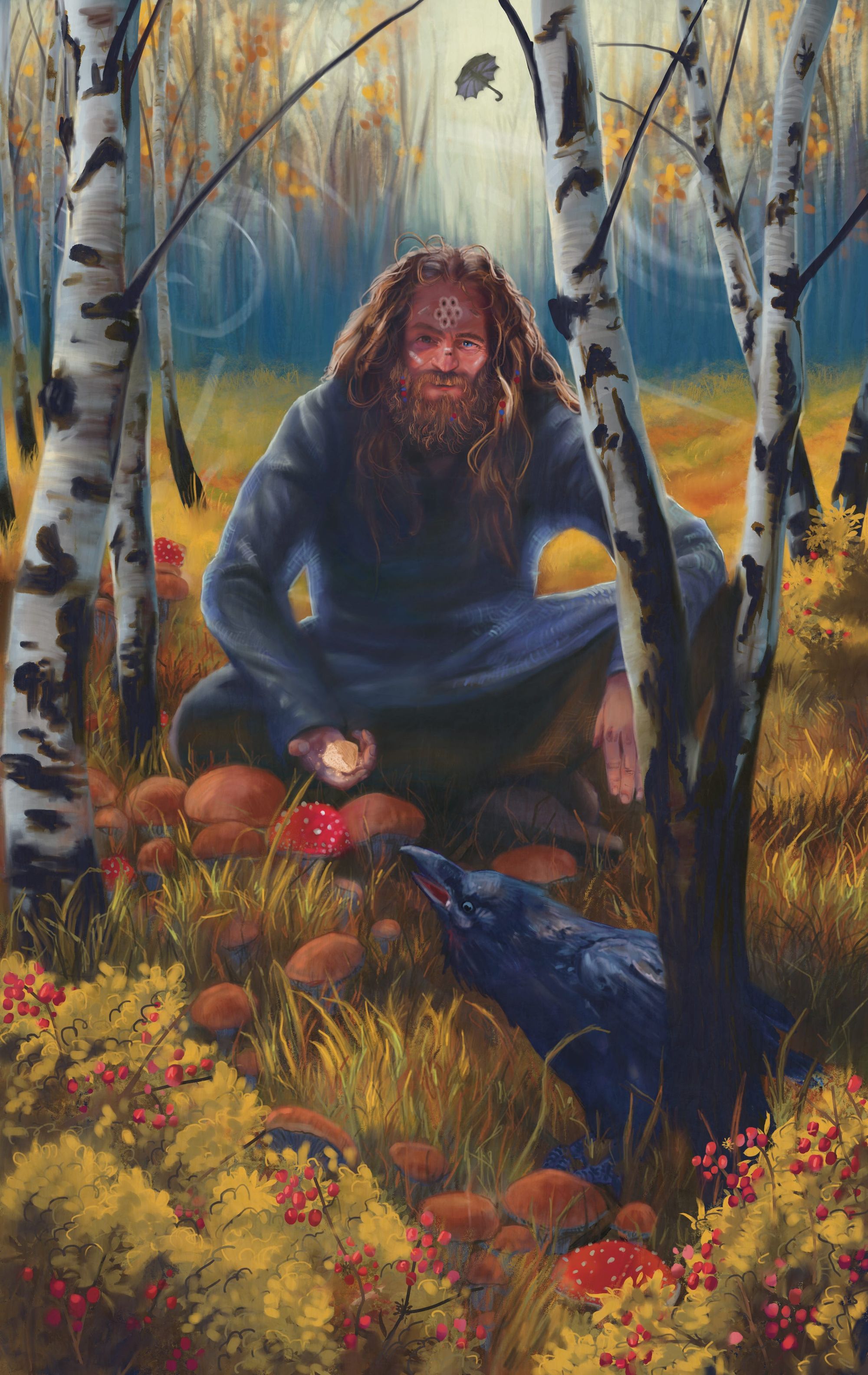

’s artwork made for the story.

Sublime was the image of the Universe, its beauty seen without a need in his third eye. Kondraty sprawled out on the grass, rusty and brisk, and, basking in the setting sun and benign breeze, beheld it, marvelled, dazed and charmed. Deep dark yet full of colour spots, wherein the light refracted like in a pool of petrol, stars floated and glimmered coyly, as if the Universe breathed with a slow hypnotic movement. Galactic textures soothed his eye and stirred his thought, beguiled his spirit. Somewhere there among the stars, was one that warmed him; near it—a planet blue, where laid his body, a nullity in human form, frozen in time and space, abased, far from the infinite eternal. That thought and view impaled his mind. Just wow, he reckoned, how have I missed that all the time? The perfectest perfect of perfectly perfect perfects, eat me, Universe. Why are we so craven to explore…?

Behind Kondraty, landed a stately stygian raven, its left wing striped with white, its eyes alike charcoals, its beak alike a blade, ominous, sharp, obsidian-made.

Encroaching on Kondraty's solitude, the raven uttered:

—Krraa.

—Oh, hi, birdie! Such a mesmerising view we got here, huh?

Inside his mind, he named all animals he saw: squirrels and starlings, ravens, rats, wood pigeons, foxes, frogs, et cetera. Some were his friends, some foes, some passersby, some food, some interlocutors, the others – messengers. This raven, not a random bird, but a new friend, was no exception and with no retort and choice accepted “Kutkh” to be his name. Kookily, tilted Kutkh his head, tousled his plumage, stared back.

—Kraaa, the raven cawed.

—Kraaa indeed, my droog. I know, I know, one seldom can be full with only Beauty, Kondraty said, and sat and took his bag, a ramshackle rucksack.

Above, the golden crowns of birches flashed and rustled warningly, and the wind Boreas grabbed Kondraty's beloved umbrella with that perfectly perfect, facsimile image of the Universe painted on it, and the umbrella fled into the birchwood corridor made of white and black stripes, the corridor optically infinite. Jingling the runic rosary interwoven into his hair and beard, Kondraty, hopping and stumbling, tangling in his baggy clothes, chased the umbrella. Alas, Boreas was a moron, a moron mocking, a faster moron, a moron stronger. Right at a ravine where below streamed a river, the Universe ascended like a plane, spewing diminishing he-he-he's, flew higher and further above the trees, somewhere Kondraty knew no whither. Panting, he stopped and spat.

—I'll find you, dear! Spreading his hands, Kondraty screamed into the birchwood wilderness, labyrinthine and golden, hidden beyond the ravine, with no beginning or end to establish.

He spat again and, stomping, returned to Kutkh.

—Can you imagine? Boreas, that bastard, stole my Universe! My Universe! Imagine!

He spat again, picked up the rucksack and threw its only strap over his shoulder. With curious countenance, Kutkh kept inspecting him.

—What? I'm leaving. It's going to be a wee bit too much chilly to sleep in here, my droog,' said Kondraty, shivering skittishly.

—Kraaa, kraaa! Cawed Kutkh, jumping, and fluttering his wings.

—Ah, the food!

Kondraty made the eureka gesture.

—Well, you're lucky I'm fasting today, huh!

Inside his rucksack, he fumbled. He pulled out a half-loaf of bread, or rather a rusk, sprinkling crumbs, tore a small piece from it and handed it to Kutkh. Incredulously, the raven jumped back, but then snatched it and hurried away.

—Oh, yes, thank you, too, Kutkh! Enjoy your meal, by the way!

Alas, no answer given, the raven dissolved in the birchwood.

By dusk, returned Kondraty to his mattress under the unfinished highway' bridge, a border where ended the realm of birches and started the city, where grey took over gold. No wind, no chill, instead, a makeshift hearth made by the others. Accustomed were to silence they, and feeling that was mutual. Their language was unspoken, by nods and glances played. In blankets wrapped, hairy, dishevelled, in semblance of a ritual, they huddled, slept or entertained their eyes and minds with dancing tongues of flame and crackling embers. They were like imps, locked longing in their den, awaiting to be mustered. Kondraty nestled on the sideline. For them, in all his outfits and demeanour, he appeared an exemplar of a menagerie or circus. No fun they made nor mocked him, no, apart from Kondraty’s intent, the awe at the unfathomable cased the social distance: his ginger mane with rosary entwined, his face painted with coal and chalk, and a ꙮ, a multiocular O, a little inflorescence of monads, on his forehead. He did look like no bum, no vagabond, no junkie, no man in misery, no, he looked an ancient volkhv, a hitchhiker from unseen dimensions, for whom the mattress, the bridge, the makeshift hearth, were bringing joy, at least until that day. That day there was no umbrella. Found in a dump, outwardly commonplace, inwardly sui generis, the umbrella subdued his mind, became an artefact, a talisman, even a friend, acquired an eminent domain over his consciousness and all beyond it. He used to place it between him and the hearth and his underdog friends. The plain back outer part was shielding him from their curious eyes, and the inside where the Universe hid served as a source of reveries. Hooked to infinity, he dived into the cosmic scenery, transporting his mind there, at first – awake, later – in dreams, but on that day… Boreas stole it all. He frowned, growled and grimaced and turned facing the wall. He mumbled, scribbled Duhstuh runes with chalk on the concrete, tried to evoke a dream, any dream, better so – a dream of the Universe again, but vainly. The runes that day declared no word, the symbols formed no meanings, Kondraty's mind was still on Earth, inside his head, imprisoned in the skull bones. That day, a good night's sleep was not forthcoming. . .

. . . Then, followed the morrow. Someone sprayed the vegetation with the drops of sorrow, someone covered whiteblack trees with an eerie fog, teary, sticky, cold, leaving none in sight beyond one’s hand, none in mind inside one’s head. Golden was the ground, golden was the sky, monochrome was the visible horizontality. But Kondraty knew the way. Snapping twigs, tinkling rosary and beads, his body interspersed with birches, wobbling his way throw their multidimensional striped fence. From under their coloured caps, mushrooms peeked and lapsed as Kondraty passed them, for their imminent end in his hands they foresaw, but that day they were safe, for he sought the Universe, nothing more. He met a large, bulky oak and said, lifting his head:

—Hey, my friend, have you seen the Universe around here lately?

The tree shook its crown, leaves rustling, bark cracking.

—No? You haven’t? Shame, eh… Alright, I’ll keep looking then. Thanks, anywise.

Kondraty saluted to the oak and moved further. On his way, he asked every tall tree, for only they could see high enough, far enough, both in space and time. At times, he paused his journey to hug one of them or chat about things mundane, about the weather, about the transience of time, and if the world was sane. He approached the ravine long and deep, dividing the birchwood in two parts, and looked down. Beneath, among the dead trees and scrubs, chirped the brook, its cold streams sleeked the pebbles.

—Morrow to you, little river. By any chance, have you seen the Universe? … No? It hides inside an umbrella, by the way.

The brook splashed, simpered and rolled onwards. Well, alas. Kondraty shrugged.

—Thanks, anywise!

Using a fallen birch, he crossed the ravine and entered the realm of blackberry and nettle. Through thickets waded he for hours, yet no signs of the Universe revealed them and no bush nor tree nor stone nor mushroom witnessed it. Boreas stole and secreted it, and now it was lost. Lost was his mind, lost thoughts lurked through the convolutions. What if somebody found it? Would they handle the beauty, the knowledge, the higher energies it emanates, the view sublime? No one could possibly withstand that. And what if a squirrel sees it? Well… Kondraty gave up, and hungry, tired and frustrated returned to his everyday deeds. . .

. . . Deep in the wilderness of birchwoodness, secluded in a quiet grove under the golden canopy, he made a fireplace and, sitting in the lotus pose, was brewing a concoction of various plants and mushrooms he'd gathered earlier, leading a ladle slowly, lovingly inside a small pot. What was the recipe? No clue – it was Kondraty's secret brew, his chef's special. No one was ever granted a chance to know parts of the mixture, moreover a casual observer. For Kondraty, the value of plants and shrooms was determined by their ability to warp the perception. Some were for the mind, some were for the taste buds. Together, they formed the uniquely uniquest blend of unique uniquenesses. The cooking process required one full day, aside from the time of gathering and drying. He could've shopped for them, yes, but seldom he had any money or the idea of that. Crucial was having a raw organic product picked with his bare hand in the place of positive energies. After hours of slow brewing, the concoction needed some time in a cold, dark place to acquire its psychoactive properties. He drank it to tune his mind to the currents of universal consciousness permeating everything around, somewhere denser, somewhere sparser. From those currents, using a metaphysical ladle, he could draw arcana, and then fulfil his mission of enlightening people, giving them a chance to discover more about the Universe, conscious, unconscious, subconscious, metaconscious, hyperconscious and some other consciousness types. Regrettably, few eager were that knowledge to accept.

Upwards, Boreas, sneaky bastard, embraced the birches’ crowns and played with them, pressing its fingers on their countless leaves. Rustling cascadingly, the birch choir whispered.

—Good afternoon to you my dear Kondraty, in our humble grove we welcome you.

—Hello, Kondraty grunted.

—Your life, how is it? We weirdly feel it's been a blink since your last visit.

—You, trees, always say that. So-so. I’m mourning. Have you seen the Universe?

—The Universe?

—Yes, the Universe.

—It everywhere is, it nowhere ends.

—I know. I mean mine, my Universe. In the umbrella.

—In the days of yore, we’ve seen it, yes. You bring it here always. With you, it is on a day that happens.

—Today is not that day. Boreas stole it, sneaky bastard.

—What’s lost, once to be found.

—Not if it’s stolen.

—Don’t argue with those for whom the time-space continuum is merely a landscape.

—Are you spoiling me a plot right now?

—No plot there is, it’s only ripples and circles on the water, spreading quaquaversally, escaping the pebble thrown.

—Thank you. This is incredibly helpful insight, I can’t even describe how helpful that is. But I’m a bit busy.

Kondraty scooped a ladleful of green-brown liquid up from the pot and brought it to his face, inhaling the aromas. They creeped inside his nostrils and heated his airways, blurring his sight, destabilising it and narrowing. The currents bent, twisted and wrapped around him. He closed his eyes, blew on the ladle, prepared to sip… but flinched and spilled the hot concoction on his crossed legs (whoops!). Near to the fireplace, a raven landed, smashing his sudden presence on the harmony and sending the tongues of flame adance.

—Eat me Universe! You, bastard! I've almost pooped myself. Do you know what's privacy, aye?

It was Kutkh. That one white feather had revealed him. The raven posed in front of him, watching and waiting. His plumage shined and shimmered ebony and blue lobelia, his eyes contained the night, his beak—a rolled piece of paper. He dropped it, cawed and, swirling a golden hurricane, surged upwards and faded. Kondraty covered the сoncoction with his hands and when the dust and leaves had settled, raised, picked up the piece of paper and unrolled it. A banknote, a tenner, money. Oh, well. What am I supposed to do with it? He thought.

—Hey! What am I supposed to do with it?

No answer followed. He shook his head, pocketed the tenner and returned to brewing. Soon, the concoction blackened, thickened, acquired the consistency of syrup. Kondraty split it evenly into small jars with airtight seal locks and, wrapping them in a blanket, buried in his underbirch stash nearby, a small pit he dug one day. He extinguished the fireplace, packed up, glanced over the grove, wished a good while to the wise birch, and headed to the city. . .

. . . The city was oversized, oversized enough for people to habitually ignore each other, except Kondraty. Among the commoners, he was a freak. Among the freaks, he was king. King Kondraty, first of his name, The Seeing, The Hearing, The Feeling, The Wandering, the lord of the unseen dimensions. As he strolled through the city's streets people's attention contorted: faces changed, wrinkles smoothed, jaws dropped, eyes widened, hearts stopped for a moment and souls trembled like leaves in the wind. Whether moving or standing still, they turned their heads at uncanny angles, following Kondraty passing them. He couldn't be missed or mistaken for someone else, for his every step produced copious sounds. Equipment rattled in his rucksack, the runic rosary and beads jingled, boots scuffed the pavement. Sometimes, under curious looks, he could sharply turn his head and stare back at the beholders, smirk cartoonishly, raising the outer sides of his brows, or wave his hand, wiggling fingers, appearing skittish and creepy. Yet, ordinarily, he ignored such looks, not on purpose, he wasn’t aware of them, for muddled was his grey matter, amalgamated with swarming thoughts.

Some called Kondraty a charlatan, a madman, a poseur, or a shmagus—few sensed the aura he emanated. For them, he was a teacher spiritual, a sage, a clairvoyant, the prophet wisest. On those occasions, humble and coy he was, excused himself, and said that he was just a Kondraty and no one else, nor was he channelling the will nor someone's maxims. He was merely a Kondraty, one of many random Kondraty’s that could’ve existed, in fact, everyone could’ve been a Kondraty if they wanted willingly, equally, Kondraty could’ve been everyone; hence to transcend, they must’ve accepted that, they must’ve accepted the simple fact they were listening to someone like them, a creature trembling, a person saying all in his name, not covering himself up in the name of supreme powers. There was only a Kondraty and the infinity of the Universe, the universal consciousness of all living beings, spreading everywhere, ending nowhere, and his mind was just a tiny breach in it, a keyhole in the door through which he peeked to see something no other human could. Sometimes, behind the door there was another door, and another, and another, and another. The doors were, in fact, infinite. They were of different colour, different pattern, different shape. They were floating always, each of them in their eigen direction, either left to right, either slow or fast, and all you could see through the keyhole of the very first door is the second door, displaced, but—sometimes magically, sometimes obeying to efforts of beholder—keyholes aligned, and through one keyhole the one could see another keyhole, and another, and another, and another, and so to infinity, until what had to be seen was seen, but it must’ve been looked at carefully. This would've sounded more convincing if Kondraty said it to you directly, for no written words could possibly convey his mellow expression, the depth of his blue eyes and movements of his face when he was looking inside you and giving birth to those infant words above. If not his heroic humbleness and seclusive detachment, he could've been rich, he could've built a cult around himself, but his prominence remained niche among those few people. Things sacred shall be free, for otherwise, what’s sacred about them? He used to say.

The grief for the umbrella did not fade, but thought about the tenner soothed it. If ever was he friends to money, it dumped him for his passivity. What do people buy? How? Dither it made him he, uneasy. Whenever lucres surfaced in his life, his first thought was of new equipment: jars, lighters, chalk, et cetera. The next thought was of substances, mind-altering, or better so mind-mending, psychoactive catalysts for his psychomagical voyage, but the tenner was not enough. Then food, perhaps? That wouldn't hurt. What do ravens eat?

He stopped by a bakery and stared through the shop window onto the assortment of cakes and muffins, sandwiches layered neatly on a large serving board, lumps, and slices of sourdough and pillars of baguettes resting in wicker baskets among the wooden interior. The doorbell rang, the rosary jingled, Kondraty walked through the door. A wryly smiling cashier met him. He pointed onto a seeded sourdough, prepared the tenner, but, before paying, a peculiar culinary idea betided in his mind and, leaving behind the confused cashier, he hurried out of the bakery to a different shop. . .

. . . Deep in the woods, there was a pond, a peaceful water basin, where willows overhang above the reeds, and constellations of nymphaea, nymphaea alba rising from the primeval slime, bloomed. At night, a bloody massacre developed there, an infringement on nature, a hunt for frogs. Kondraty, equipped with a hand net, naked, hid in the reeds, waited. For hours, he waited for frogs to join crickets in their nightly song, meanwhile, dazed, gazed at the nymphaea. Towards the moon their petals unfolding, they reminded Kondraty of his umbrella, the same but with a handle reversed. Perhaps, it also camouflaged in a pond somewhere pretending to be a nymphaeum, and there at night opened its oculus upwards to the sky, speaking to it, or screaming, in desperate and painful screams, pleading to Kondraty to be its saviour. Hypnotised, mesmerised, sleepy, with no ticks of time tracked, he submerged into dreams and almost missed when the croaking commenced. The croakers, they gathered on nymphaea leaves, in reeds, on stones, onshore. He saw them, his victims, brown and green, spotted dark. He snuck up and swung with the net, transferred the frogs to his sack, and once more, he snuck up and swung with the net, splashing water, drowning the nymphaea's leaves, he snuck up and swung with the net. Thus passed a few hours, the pond became quieter by a few a dozen of croakers. . .

. . . At dawn, in his grove, yawning Kondraty immersed into culinary adventures. On his improvised stove, boiling were two pots. In the first one, in spring water, the poisonous substances were being expelled from the nymphaea alba. This was for Kondraty. In the second one, the frogs were being fried deep, lightly breaded, salted, peppered, submerged into three hundred millimetres of extra virgin and extra premium olive oil that he bought instead of bread. This was for Kutkh. Once a frog acquired required crispiness, Kondraty transferred it to the wooden bowl beside him and put another one into the oil using chopsticks, those wrapped in paper that Asian restaurants add to your order all the time. Surely, forks and other cutlery were in Kondraty’s possession, but only chopsticks could help to transfer frogs from the pot to the bowl keeping their little bodies intact, avoiding boiling oil splashing. Soon, frog by frog, the exotic breakfast came to life.

Kondraty sat under a birch, surrounded by a mushroom mob – leccinum scabrum, amanita muscaria, of different size. He chewed the nymphaea and thought of the umbrella, of winter soon approaching, and whether deigned to visit him the raven. At times, he pondered the infinite eternal, a wee bit. Under a towel, the frogs fried deep were cooling down. Kondraty frowned and raised his head up to the sun to tell the time. Kutkh was late. He closed his eyes and imbued his lungs with the morning chill.

—Kra-a-a-a-a-a-a, the raven’s caw reverberated across the grove, and near Kondraty, Kutkh emerged.

Here he is, the master of arrivals sudden, even if you're expecting him, thought Kondraty, smiling.

—How have you been, my droog?

Kutkh stared at him, tilting his head, waiting.

—Kra!

—Good, good. Look—

Kondraty took one fried frog from the bowl.

—This is for you. I made it, said he, and hurled it to Kutkh.

In flight, the raven caught the frog, clutching it in his beak, and, a second later, devoured the treat.

—Kra-a-a-a-a-a-a!

—Is that “thank you”, or “more”?

—Kra-a-a!

—Ah, both.

Another frog Kondraty gave him, another and another. Thus, frog by frog, devoured he everything as if a black hole was inside his stomach or frogs were made from air. Ravenous bird was Kutkh.

—Kraa!

The raven bowed, wingswung, and flew away. Again, alone Kondraty was, he and the boiled nymphaea.

Soon, the kinship of the vagrant and the raven reached a new, unprecedented level. The morrow followed and again there was a banknote in the raven's beak, this time – fifty. Reluctantly, Kondraty took the boon. A few times a week he went to the city to buy some equipment, spirits for tinctures, empty bottles and jars, and more olive oil. Nights he spent at the lake naked, bringing frogs and nymphaea to the edge of extinction. Cold were those nights, but he neglected the bridge and the human friends, instead, those minor hours of his sleep moved to the birchgrove, where in a tent made of the things abandoned, curled up in bliss, he dreamed, warmed by the smouldering fire. At dawns, he cooked, then sat and waited, trepidated, each time afresh. The raven came and brought new boons, they sat and ate keeping a stern decorum, at times chatting and bantering in the corvus lingua about the things mundane, about the weather, about the transience of time, and if the world was sane. . . .

. . . When matured the concoction, matured the time for the ritual. Kondraty knew it couldn't be the same without the umbrella, but it could be even better with the raven. He took the jars out of the dugout and opened one of them. An odour of the dark slurry invaded the air, and Kondraty invited it into himself. The pungent smell hit his receptors, he twitched, his cheekbones and every muscle in his face cramped. Almost fainting and loosing consciousness, he staggered off, crushed a couple of flyswatters and leaned against a birch tree, breathing heavily, his bloodpumping system overdoing its job. Wow, he thought, the perfectest perfect of perfectly perfect perfects. Eat me, Raven. Covering his nose, Kondraty closed the jar and hid it in his pocket. From the pouch, he took out a collection of dried herbs and dumped it into the embers. The embers puffed, hissed, farted. Smoke ran from them, and enchanting aromas usurped the grove. Kondraty took the runepebbles and emplaced them round the fireplace. Now, everything was prepared and ready, all that was left was to wait for the raven. Kondraty assumed a waiting pose and began to wait. Thus, he sat for an indefinable number of moments, not doing much, just casually being hooked to infinity.

Kutkh appeared just in time. He landed next to Kondraty, cutting through the brume of smouldering herbs.

—Kra-a-a kra'a-kra'a, cawed Kutkh, and produced a sound a hit sheet of iron produces.

—Kra-a kra-a, cawed Kondraty, nodding.

—Kra-a r-rakka kra? Cawed Kutkh.

—Kra-Kra r-rakka, cawed Kondraty and patted the earth, inviting Kutkh to approach him.

—Kr-r-a'a

—Kra

—Kra-kra-kra

—Kra

Through the smoke, the raven walked, and, approaching Kondraty, raised at him the dark coals of his eyes.

—Kra'a, cawed Kondraty and placed the concoction jar beside Kutkh. Kra-aa-a, he added.

At the jar the raven looked, at Kondraty, shook his head, and immersed his beak into the dark slurry. He ruffled his feathers, began flapping his wings and cawing, again and again—it was a caw of wonder, a bustling cry, the one of thunder on a stormy day. Kondraty, face asmile, patted the raven. Then he took the jar and quaffed its content. Immediately, the surrounding smoke formed a vortex, the birches' crowns began to rustle. Kondraty's eyes turned white, he threw his head back and then… emptiness, the utter void of unconsciousness. . .

. . . Kondraty woke up, yawned, stretched, scratched his nose, and felt the absence of the ground. Startled, he unsealed his slimy eyes and realised that he was uncontrollably flying, much so. The ground was still there, but far away beneath. He couldn't concentrate to understand what was happening, for the environment moved too fast, as if in front of him there was a colossal spinning globe. Someone sped up the Earth. Boreas, bastard. Once vision bettered, downwards he saw the city and a river across it, all in one big miniature enclosed in golden endlessness. Now, he was flying above the river. Flickered its surface, glared, moving as fast as the city, the birchwood, the globe, yet in the opposite direction. The river flowed in reverse. So it seemed. Perhaps because it also reflected the cloud running above, turning the illusion more optical and the optics more illusionary. Kondraty saw his own shadow, a large silhouette travelling on the water surface together with him. He waved to it. The silhouette waved back. Kondraty smiled. Then he saw it—the silhouette was surrounded by birds, ravens, countless in their quantity, orderless in their position. Crunching his neck, he lifted his head to see them. Clawing at his clothes, they carried him. Some flew next to him, somersaulting. All cawed. Oye, there was sound, loud sound, almost deafening, he realised late. Reverberated the holler of ravens, chaotic and hellish, mixing with the swishing wind. Kondraty screamed, cawed, wheezing and gasping for air. Synchronously, the ravens gleamed their dark eyes and stared at him. He flinched. The ravens grasped firmer and pulled him farther up. He looked down. The ground was bidding farewell to him. Goodbye, Kondraty, bon voyage, spoke the people, the river, the trees, the ground itself. On it, his diminishing shadow had wings, wings enormous. Again, he turned his head as much as he could. Above, was gliding Kutkh. His dimensions, they were amplified. His body was as big as Kondraty's, his wingspan embraced half of the sky. Kondraty blinked and rubbed his eyes. Kutkh' size remained the same.

—Kra-a-a! cawed the raven, flapped his wings and overtook Kondraty.

They traversed the city and now flew above the golden sea. Kutkh was leading the flock, now flying slightly beneath them, just above the trees, almost touching their crowns, and the sea rippled. Transcendental was the moment, grandiose, lasting for eternity, and in its timespan, every possibility happened—meaninglessness became meaningful, meaningfulness became revelatory, lives became inane, emptiness became matter, matter became incorporeal, galaxies appeared and slammed shut—the Universe was expanding. Yet, at that moment, Kondraty's head was empty. Someone removed his brain, leaving only what was supposed to be there—the primordial void. In that primordial void, when it suddenly grew bored with itself, a thought was born, a daring flash, an arrogant spark, an aspiring supernova. Kondraty extended his arm towards Kutkh, wiggled, and gutsily jerked ahead. Loosened the ravens' grip, and he fell down, squeezing his eyes in fear, and in the next moment appeared on Kutkh's back.

—Kra-a-a-a-a-a!

The sky darkened, roared the thunder, blazed the lightning. Or lightnings? Another "Kra-a-a-a-a-a!" rumbled, even louder, vibrating and ravenberating through each bone of Kondraty's body. His teeth rattled, drumming at two hundred and thirty-three beats a minute. A dark vignette started circling over his sight. His eyelids tight aclench, Kondraty dipped his fingers into the silky plumage and clawed, clutched spasmodically.

—Kra-a-a-a-a!

Kutkh spiralled and turned over. His corpus started changing. Eyes bloomed on it, copious oculars, a trypophobic nightmare. All, stared the eyes into Kondraty' soul. He was paralysed. His fingers forgot how to grip, he collapsed into the golden sea, seeing how the ravens hovered over forming a circle with multiocular Kutkh acentre, all of his copious eyes blinking. All at once.

First, came the sensation of pain, the nagging physical discomfort created by the total sum of bruises, scrapes, and sprains acquired from hitting the birches' branches he had knocked down in flight, remnants of which were now lying around the bush whereon he landed. Then, he opened his eyes. Leaves fell down like snow or ashes, moving in spirals, zigzags, and loops. Trunks of the birches painted a tunnel, a black striped perspective onto a patch of clear blue sky amidst their golden crowns. His nostrils steamed, his mouth, too. Creeps crawled up his corpus. But none of it mattered. The birchwood welcomed him with serenity. . .

. . . In a state of oblivion, Kondraty rested until the sun rolled into the blue patch above, a hole in the golden crowns, closing a door wherefrom he had fallen. The autumn sun is not warming yet bright. He closed his eyes and the red pictures appeared in front of him. He squinted and relaxed, controlling the gradient, and the red pictures assumed new, unbeknownst forms, disappearing and appearing again, yet still preserving the silhouette of the birch tunnel visible, but then, the pictures started flashing. Kondraty opened his eyes again and saw Kutkh of his normal eyeless form. Silent and ghastly grim, the raven was graciously gliding down. In his talons, he carried something black.

—Kr-r-a… wheezed Kondraty.

Yet no answer gave the raven. A few more circles after, he dropped the item, swooped down and disappeared between the birches.

Kondraty tried to sit, then stand, struggling and feeling that total ache-sum, but approached the item. It was the umbrella, folded. He picked it up, pushed the button and the umbrella opened. Inside, as if looking at him from the centre of the umbrella’s hat, wherefrom the handle was growing, sat a large black dot beset by the infiniteness of tiny stars and planets. The view was the same as the last time he saw it, except it now felt different. It was truly alive. The whole image breathed, moved, drifted dizzily. Bereft of its past staticness, it seemed a portal, a door which was revealed to him, and which he was supposed to enter, by himself. Kondraty stopped blinking and stiffened. The raven brought the Universe back to his knees, and now its image was more sublime than ever, opening its oculus to him. He stared at it, inside it, beyond it, benumbed, his eyes agape.

—Kra! uttered the Universe.