I stumbled upon one curious text while reading and studying James Joyce's Ulysses (quite slowly, though) and learning about Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein and his great contribution to cinema and film theory. The text you'll see above is my translation of an autobiographical note of memoiristic and diary nature written by Eisenstein in preparation for his unfinished book Method.

This text is steeped in the spirit of the Roaring Twenties and old Paris and gives a chance to learn something new about that era and two great artists, Sergei Eisenstein and James Joyce, their lives and encounters with each other.

I put notes, mine and from the original Russian page I found, for you to learn more and understand the context and some of my translator’s choices better. I haven’t checked if it was already translated before by someone (I was so eager to do it myself), so if you by any chance have read it already I’d be happy to read that translation, too.

So, we shall begin.

The year the thought about "intellectual cinema" is born is also the year I meet with Joyce's Ulysses. First from the brief prospectus1 in subscriptions to the German translation edition. But even this prospectus turns my head. Later (in the jubilee days of the 1927 year2) I stumble upon the only English edition of Ulysses in Moscow. And after the first visit of the Soviet delegation to Geneva, I become the independent owner of my own copy of the book3.

Why is Ulysses captivating?

The inimitable sensuality of the effects of the text (which far surpasses the passionate sensual charm of my beloved Zola4). And that "asyntactic" nature of his writing, buoyed from the bedrock of inner speech, which each of us speaks in a special way and which only Joyce's literary genius has managed to put into the foundation of his method of literary writing. All in all, Joyce does in his linguistic kitchen of literature what I rave about in relation to my laboratory pursuits of film language.

Joyce had predecessors.

He named them himself: Dostoevsky, for the content of his inner monologues, and Édouard Dujardin, for the technique and manner of writing through the structure peculiar to inner speech5.

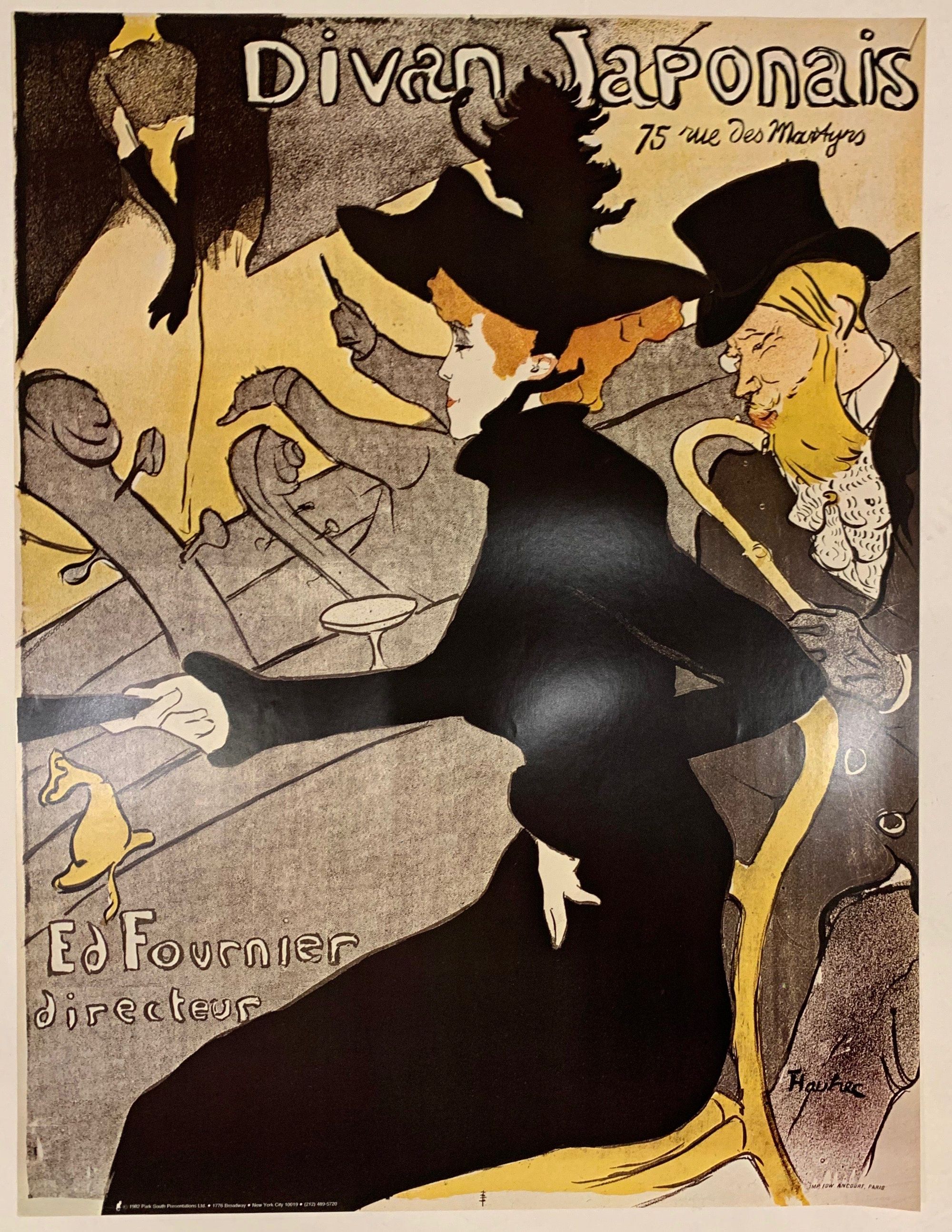

This is the Dujardin in one of Toulouse-Lautrec's most sumptuous posters, Le Divan Japonais (1892), which advertised this popular entertainment venue.

In the centre of it, the black silhouetted dancer Jane Avril6 in a party dress; to the left, in the corner with her head cut off by the top edge of the poster, but nevertheless unmistakable, is the star of Le divan Japonais Yvette Gilbert7 singing a song. Two contrabass fingerboards. A cocktail glass.

In the right corner, the blond dandy in a cylinder. Monocled. The silky beard blends in with the mottled tie. The dashing curve of his rounded cane handle strokes his sensual lips lovingly, his eyes indifferent to Yvette, but fixed on Miss Avril's lower part. He looks much the same, only without the irony, in someone's etching8 from 1888, a year after the first edition of his book was published.

This way Dujardin's figure whimsically combines a pioneering work of inner monologue with two characters that I would most like to meet in Paris. James Joyce and... Yvette Gilbert! <...>

To meet Yvette Guilbert is to touch the most charming era of Paris...

We met. But the description of this wonderful, colourful encounter is certainly beyond the scope of this article. Let's postpone it until another time.

I met Joyce as well.

He is no longer alive now and I can no longer overcome with a new encounter the sad details of the farewell we had.

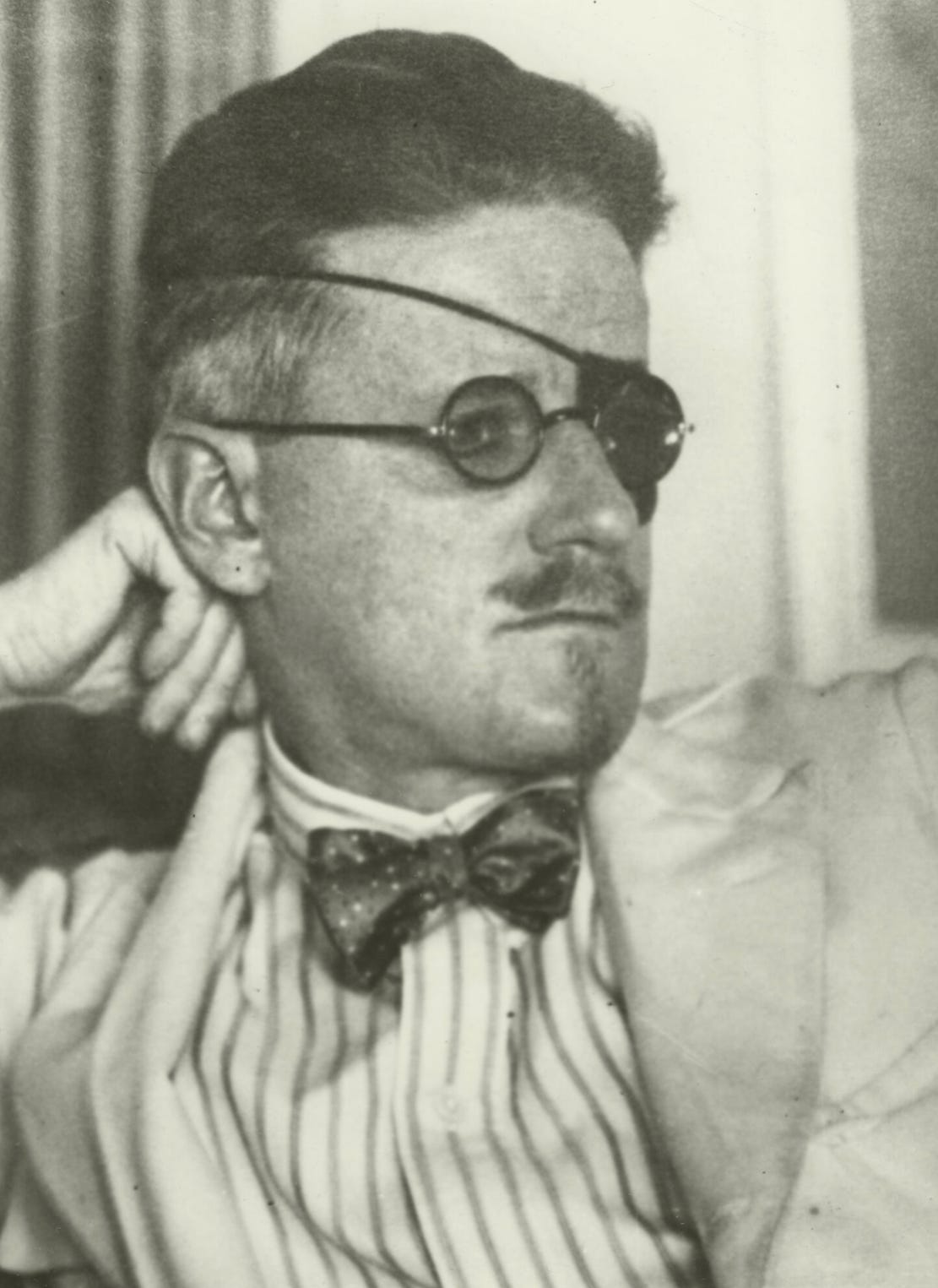

Saying goodbye in the narrow hallway of his light-coloured flat (as I remember even now the striped wallpaper of the hallway, white matt with white glossy), saying goodbye to me, this tall and slightly stooped man, almost without facade – so sharp is his profile of reddish skin and fiery and thickly greyed hair – waves his hands strangely and fumbles through the air.

Surprised, I ask him what is wrong.

"But you must have your coat somewhere...," Joyce replies and fumbles around the walls.

Only now do I realise to what extent was weak the vision in relation to the outside world of that almost blind man, whose blindness, perhaps, accounted for that special sharpness of inner vision with which inner life is described in Ulysses (and in A Young Artist9) with the remarkable method of inner speech.

I get insanely uncomfortable.

Just a moment ago, he was eagerly asking me to show him my films, interested in my experiments in cinematographic language on the screen (in the same way I am fascinated by his kindred literary pursuits).

He has just signed me a copy of Ulysses.

Only upon arriving home and opening the book cover, did I see on the first page almost unreadable marks and the date (30 of November 1929), obviously written from memory (wasn't that why he walk with the copy to another room where he spent so much time on three words of dedication, two of which are the name and surname, and the third is the city – Paris!). So I myself, like a blind man, spent almost the whole evening with the almost blind man not seeing, not sensing and not noticing it! <...>

...What brings me out of my awkwardness is our third interlocutor. It's some suspicious Russian with a lackey's face. Probably, an émigré. And maybe also a spy.

It's somehow natural to put a coat on from his hands!

Joyce hired him to study... Russian language. 10

The linguistic work following Ulysses will reflect the birth out of the general chaos of separate languages and will be written as a fusion of undifferentiated linguistic elements. The Russian language is also needed in this fusion.

This work is Work in Progress11, and Joyce's smooth voice reads a fragment of it (Anna Livia Plurabella) to me.

"But isn't Joyce blind?" an attentive and benevolent readeress12 would ask, precisely a readeress; a readeress and only a readeress would have noticed that.

Calm down, readeress.

And thus the voice reads... sounding from the pathéphone Joyces winds up.

Anna Livia Plurabella recently came out in a tiny book as a separate edition13. A fragment of this fragment of the future thing Joyce “narrated” onto the record.

Thus I follow the spoken text on the gigantic one-meter sheet filled with gigantic lines of gigantic letters. These are those enlarged tables of miniature pages of the tiny book, which Joyce used to reinforce his memory while narrating the record.

That exaggerated size of a miniature page of a miniature book fragment!

It is in the image of the author. It is in the mode of the magnifying glass with which he traverses the microscopic windings of the mysteries of literary writing. How emblematic of the ways in which he wanders through the windings of the inner movement of emotions and the inner structure of inner speech!

The new meeting doesn't bring much. Except for the same element of direct touch that I gained later when I visited Mexico regarding anthropology.14 And, perhaps, more information that Joyce was very fond of cinema and even once ran a film distribution business, temporarily owning a small cinema in Switzerland.15

1940 – 1948

Eisenstein used the word "prospectus" which is not commonly used in Russian and English but I decided to keep it. I found "prospectus" is a programme, a list of something, a reference publication of a promotional nature, containing a detailed list of what is forthcoming or has been prepared for publication. ↩

He probably meant the 10th anniversary of Soviet power in Oct 1927. ↩

The book was brought to Eisenstein in 1928 by Ivy Litvinova (née Lowe), an English writer, wife of Soviet Deputy Foreign Minister M.M. Litvinov, who accompanied him to the Congress of the League of Nations in Geneva. ↩

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola was a French novelist, journalist, playwright ↩

Joyce's statements on Dostoevsky are contained in his 1920s conversations with the artist Arthur Power (Power A. Conversations with James Joyce. London: Millingoton, 1974). Dujardin, Édouard (1861-1949) - French novelist, poet, playwright who attempted to reproduce the "stream of consciousness" in his novel Les Lauriers sont coupés, 1887. ↩

Wiki - Jane Avril was a French can-can dancer made famous by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec through his paintings. Extremely thin, "given to jerky movements and sudden contortions", she was nicknamed La Mélinite, after an explosive ↩

Yvette Guilbert was a French cabaret singer and actress of the Belle Époque. Youtube. ↩

Wiki - Etching is traditionally the process of using strong acid or mordant to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal surface to create a design in intaglio (incised) in the metal. ↩

He means here A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Joyces first novel. ↩

This is most likely Alex Ponizovsky (1901-1944). He was the brother of Lucy Leon and the son-in-law of Paul Leon, the Russians who had the closest relationship with Joyce. Ponizovsky studied with V.V. Nabokov in Cambridge and was friends with Joyce's son George. Ponizovsky's Russian studies with Joyce began in late 1927 or early 1928. In 1932 Ponizovsky was briefly engaged to Joyce's mentally ill daughter Lucia. After one attack Lucia fell into a catatonic trance and was taken to a psychiatric hospital. Ponizovsky broke off the engagement (as S. Beckett had done before him) and relations with Joyce were temporarily strained but not broken off. During the war, he was in French territory not occupied by the Germans and set up a channel through which Nora Joyce, who was living in Zurich after her husband's death, managed to recover some of the property that was being auctioned off by their Parisian landlord. Staying in the free zone did not save Ponizovsky from death in a concentration camp. ↩

Joyce's novel Finnegans Wake was published in parts in the avant-garde magazine Transition under the title Work in Progress ↩

"A readeress" is “a woman reader". I decided to use this here. It isn't easy to translate it into English because nouns in Russian are not gender-neutral. ↩

The most famous part of the novel was published in 1928 by Crosby Gaige in New York. ↩

From Wiki – Eisenstein was fascinated by Mexico and wanted to make a film about the country. See, ¡Que viva México! ↩

At the end of 1909. Joyce opened Ireland's first Volta cinema in Dublin with money from Trieste merchants, but it did not last long. He subsequently owned small cinemas in Trieste and Zurich. ↩