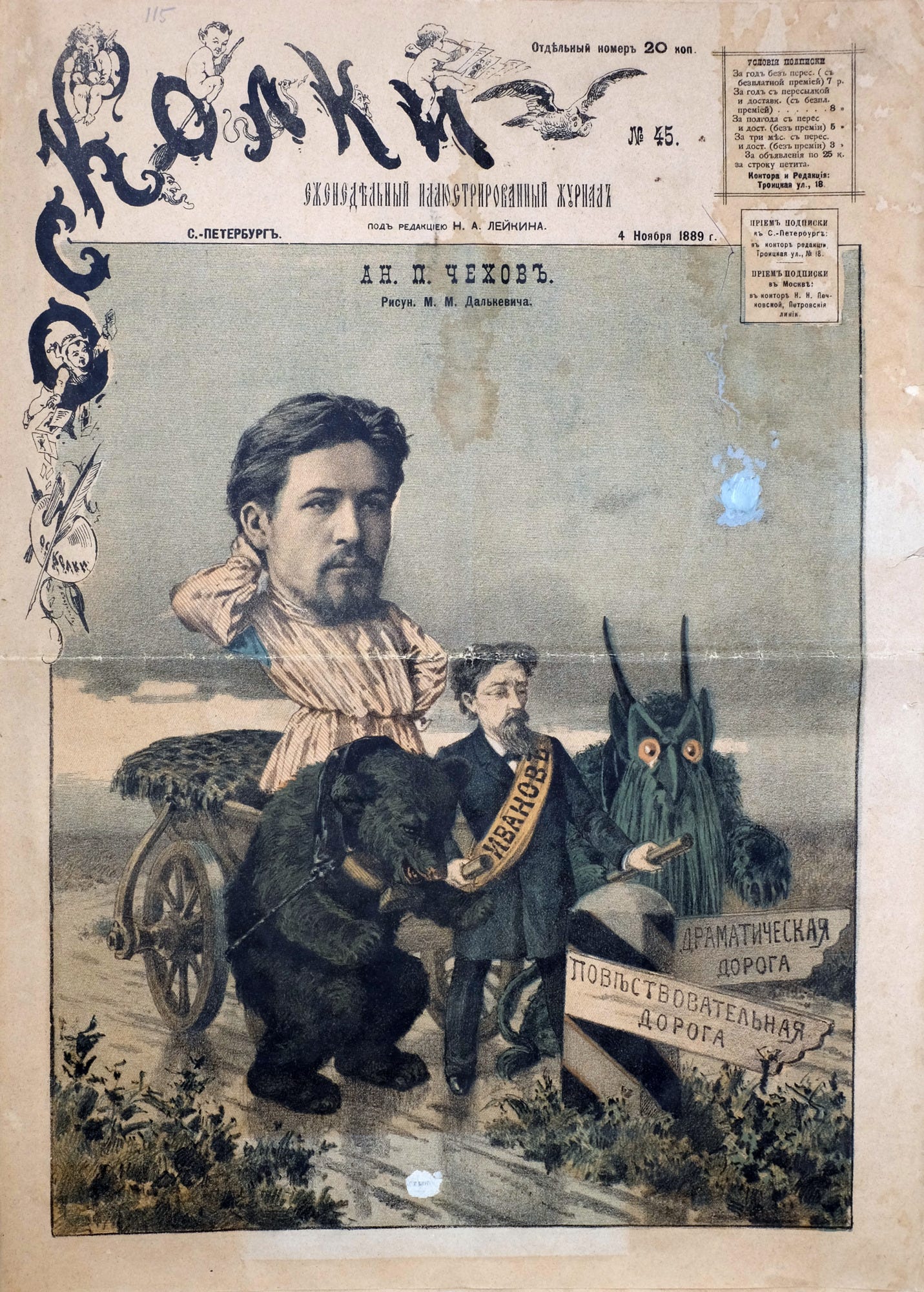

Anton Chekhov's “Drama” was first published in 1887 in the magazine "Oskolki" (Fragments), Issue №24, on pages 4-5, under the name A. Chekhonte, one of the many Chekhov’s pseudonyms. The same year, it was included in the collection "Innocent Speeches". In 1891, it was published with minor modifications and abridgements in the collection "Motley Stories" (or “Variegated Stories”), and later included in the collected works of the author, published by A.F. Marx.

According to N.M. Ezhov, Chekhov borrowed the plot of the story from the playwright Viktor Petrovich Burenin. In "Drama", Chekhov satirically criticised the writing style of some authors of his time. Y. Abramov believed that it is a comical and simultaneously tragic story in which “a writer” is a portrayed as the devil who is constantly reading their works to everyone, driving the unwilling readers to despair. S.A. Vengerov wrote about the story's veracity to life but also noted its anecdotal and caricature-like qualities.

Many of Chekhov's contemporaries included "Drama" in their list of favourites. It was particularly loved by Leo Tolstoy, who “could read and listen to it endlessly”, along with other small stories by Chekhov like "The Malefactor", "Cold Blood", and others. According to S.T. Semenov, Tolstoy was so enamoured by this story that he recounted it numerous times and always laughed heartily. Ezhov also mentioned this, stating that Tolstoy, while reading "Drama", laughed wholeheartedly and recommended everyone to read this Chekhov story. When categorising the best stories of Chekhov into two types, Tolstoy classified "Drama" into the first, the best, category.

During Chekhov's lifetime, the story was translated into Bulgarian, Hungarian, German, Norwegian, Polish, Romanian, Serbian, Croatian, and Czech. In May 1896, the Czech translator Bořivoj Prusík informed Chekhov: "Many of your small stories ("Drama" and others) translated by Baroness Bila have appeared in weekly newspapers "Narodni Politika" and "Hlas Národa", etc. Be assured, esteemed writer, that few contemporary Russian authors are as beloved here as you." W.D. Childs wrote on April 20, 1898, that he had translated several of Chekhov's stories into English, including "Drama". However, in his following letter on June 19 of the same year, he reported that the publishers did not find it feasible to print them.

Sources: chekhov-lit.ru and Wikipedia.

'Pavel Vasilyevich, sir, there's some lady asking for you,' reported Luka. 'She's been waiting for a good hour...'

Pavel Vasilyevich had just finished his breakfast. Hearing of the lady, he grimaced and said, 'To the devil with her! Tell her I'm busy.'

'She, Pavel Vasilyevich, has already visited five times. Insists she must see you... She's nearly in tears.'

'Hmm... Very well, ask her into the study.'

Pavel Vasilyevich leisurely put on his frock coat, took a pen in one hand and a book in the other, and, pretending to be very busy, walked to the study. His visitor was already waiting there — a large, well-rounded lady with a red, plump face and spectacles, seeming quite distinguished and more than appropriately dressed (she was wearing a bustle with four gathers and a high hat with a ginger bird). Upon seeing the host, she rolled her eyes beneath her brow and folded her hands in prayer.

'You, of course, do not remember me,' she began in a high, masculine tenor, noticeably agitated. 'I... I had the pleasure of meeting you at the Hrutskys... I am Murashkina...'

'Uh... Um... Have a seat! What can I do for you?'

'Well, you see, I... I... — the lady continued, sitting down and getting even more agitated. — You don't remember me... I'm Murashkina... You see, I'm a great admirer of your talent, and I always enjoy reading your articles... Don't think I'm flattering, God forbid, I'm only paying tribute... Always, I always read you! To some degree, I myself have dabbled in writing, that is, of course... I wouldn't dare to call myself a writer, but... nevertheless, I’ve done my bit [1]... I've had three children's stories printed sporadically, — you haven't likely read them... I've translated a lot and... my late brother worked at "Delo"[2]'.

'So... uh... What can I do for you?'

'You see... (Murashkina lowered her eyes and blushed.) I know your talent... your views, Pavel Vasilyevich, and I'd like to know your opinion, or rather... ask for your advice. I, should I tell you, pardon pour l'expression[3], have delivered my newborn drama, and before I send it to the censors, I should like to know your opinion. Murashkina nervously, with the expression of a caught bird, rummaged through her dress and took out a large, thick notebook.

Pavel Vasilievitch liked only his own articles, and those of others, which he was about to read or listen to, always gave him the impression of a cannon-head aimed straight at his face. When he saw the notebook, he was frightened and hurried to say, 'Very well, you can leave it... I will read it.'

'Pavel Vasilievich!' murmured Murashkina seductively, rising and clasping her hands in prayer. 'I know you're busy... every minute is precious to you, and I know you're probably cursing me in your heart right now, but... please, be so kind as to let me read my drama to you now... Please, be gracious!'

'I am delighted...' Pavel Vasilievich hesitated, '...but, madam, I... I am busy... I'm about to depart now.'

'Pavel Vasilievich!' the lady moaned, and her eyes filled with tears. 'I beseech you for this sacrifice! I am impudent, I am intrusive, but please, be magnanimous! Tomorrow, I am departing for Kazan, and today I would like to know your opinion. Grant me half an hour of your attention... just half an hour! I implore you!'

Pavel Vasilievich was a doormat at heart and did not know how to refuse. When he began to suspect that the lady was going to burst into tears and kneel down, he became flustered and mumbled in confusion, 'Very well, as you wish... I shall listen... I am ready for half an hour.'

Murashkina exclaimed joyfully, took off her hat, and, sitting down, began to read. At first, she read about how the footman and the maid, while tidying up the luxurious drawing room, engaged in a lengthy conversation about Miss Anna Sergeyevna, who had built a school and a hospital in the village. Once the footman left, the maid delivered a monologue about how learning is light and ignorance is darkness; then Murashkina brought back the footman to the drawing room and made him deliver a long monologue about the general, Anna's father, who cannot tolerate his daughter's convictions, intends to marry her off to a wealthy chamberlain[4], and believes that the salvation of the people lies in complete ignorance. Afterwards, when the servants left, the lady herself appeared and addressed the audience, confessing that she had not slept all night and had been thinking about Valentin Ivanovich, the son of a poor teacher who selflessly helps his sick father. Valentin has mastered all the sciences but does not believe in friendship or love, lacks purpose in life, and longs for death, and therefore, she, the lady, must save him.

Pavel Vasilievich listened and melancholically recalled his sofa. He cast a spiteful glance at Murashkina, feeling her masculine tenor pounding on his eardrums, not understanding a thing, and thought, Damn you... Do I really need to listen to your nonsense?!... Well, what's my fault that you've written a drama? Good Lord, what a thick notebook! What a punishment!

Pavel Vasilievich glanced at the room partition where his wife's portrait hung and remembered that his wife had ordered him to buy and bring five yards of ribbon, a pound of cheese, and tooth powder to their dacha[5].

I hope I don't lose the ribbon sample, he thought. Where did I put it? I think it's in the blue jacket... And those vile flies managed to sprinkle ellipses on my wife's portrait. I'll have to order Olga to clean the glass... She's reading the XII scene, which means the end of the first act is soon. Can one really have inspiration in such heat, especially with such corpulence as that carcass? Instead of writing dramas, she should eat a cold okroshka[6] and sleep in the cellar...

'Don't you find this monologue somewhat lengthy?' Murashkina suddenly asked, lifting her gaze.

Pavel Vasilievich hadn't heard the monologue. He became flustered and replied in a guilty tone, as if it wasn't the lady but he himself who had written that monologue, 'No, no, not at all... Quite lovely...'

Murashkina beamed with happiness and continued reading: '"Anna: Analysis has consumed you. You stopped living with your heart too soon and entrusted yourself to reason. Valentin: What is the heart? It is an anatomical concept. As a conditional term for what is called emotions, I do not recognize it. Anna (embarassed): And love? Could it be that love, too, is a product of associative ideas? Tell me honestly: Have you ever loved? Valentin (with bitterness): Let us not touch upon old wounds that have not yet healed (pause). What are you pondering? Anna: It seems to me that you are unhappy."'

During the XVI scene, Pavel Vasilievich yawned and accidentally emitted a sound from his teeth, akin to the sound dogs make when they catch flies. Startled by this indecorous noise, he quickly masked it by adopting an expression of charming attentiveness. The XVII scene... When will it end? he thought. Oh, my God! If this torment continues for another ten minutes, I will cry out for backup... Unbearable!

But finally, the lady began to read faster and louder, raising her voice, and she proclaimed, 'Curtains down.'

Pavel Vasilievich breathed a sigh of relief and prepared to rise, but immediately Murashkina turned the page and continued reading: '"Act Two. The scene represents a village street. On the right, the school; on the left, the hospital. Peasants, men and women, sit on the steps of the latter."'

'Pardon,' Pavel Vasilyevich interjected. 'How many acts in total?'

'Five,' replied Murashkina, and without delay, as if fearing her listener might leave, she quickly continued: '"Valentin peers out of the school window. In the depths of the scene, we see peasants carrying their belongings into the kabak[7]."'

As a condemned man, resigned to his impending execution and convinced of the impossibility of clemency, Pavel Vasilievich no longer awaited the end, nor did he hold any hope, but only tried to keep his eyes from closing and to maintain an expression of attentiveness on his face... The future, when the lady would finish her drama and leave, seemed so distant to him that he did not even think about it.

'Bla-bla-bla-bla...' echoed Murashkina's voice in his ears. 'Bla-bla-bla... Sss...'

I forgot to take the soda, he thought. What was I thinking about? Ah, yes, the soda... Most likely, I have a gastric catarrh... It's astonishing: Smirnovsky has been drowning in vodka all day, and he still doesn't have a catarrh... Some bird landed on the window... A sparrow...

Pavel Vasilyevich made an effort to open his strained, sticky eyelids, yawned with his mouth shut, and glanced at Murashkina. She grew dim, wavered in his eyes, became a three-headed figure, and pressed her head against the ceiling...

'"Valentin. No, let me go... Anna (fearfully). Why? - Valentin (to the side). She turned pale! (to her). Don't make me explain the reasons. I would rather perish than let you know these reasons. Anna (after a pause). You cannot leave..."'

Murashkina started swelling, grew into a colossal size, and merged with the grey air of the office; only her moving mouth was visible; then suddenly she became small like a bottle, swayed, and together with the desk, disappeared into the depths of the room...

'"Valentin (holding Anna in his arms). You have resurrected me, shown me the purpose of life! You have refreshed me, like the spring rain refreshes the awakened earth! But... it is late, too late! An incurable illness gnaws at my chest..."'

Pavel Vasilyevich trembled and stared with pale, cloudy eyes at Murashkina; for a minute, he looked motionless, as if understanding nothing...

'"Scene XI. The same figures: the baron and the policeman with the witnesses... Valentin. Take me! Anna. I'm his! Take me too! Yes, take me as well! I love him, love him more than life! The baron. Anna Sergeyevna, you forget that by doing this, you ruin your own father..."'

Murashkina began to swell again... Wildly looking around, Pavel Vasilyevich raised himself, emitted a cry in an unnatural, chesty voice, grabbed the heavy paperweight from the table, and, oblivious of self, dealt a mighty blow upon Murashkina's head...

'Arrest me, I have killed her!' he said to the servants who rushed in a minute later.

The jury acquitted him.

In the original, Chekhov writes, “but nevertheless, there’s my drop of honey in the honeycomb” (in the connotation of “modest contribution”). It seemed like an idiom to me though it’s not currently used, but I couldn’t find a more flowery English alternative than “do one’s bit”. ↩︎

“Delo” (Дѣло — Dyelo) - a Russian periodic “scholarly-literary” journal, since 1869 - a “literary-political” journal. A monthly publication of the revolutionary-democratic direction, an organ of the raznochintsy radicalism. It was published in Saint Petersburg from mid-1866 to January 1888. ↩︎

French for “excuse the expression”. ↩︎

In original, “kamer junker” or valet de chambre — a courtier who served in the imperial chambers. ↩︎

a country house / a summer house. ↩︎

Okróshka (Russian: окро́шка) is a cold soup of Russian origin, which probably originated in the Volga region. ↩︎

Kabak (кабак) is Russian word for a tavern, pub, or bar. Sometimes used derogatorily to refer to a low-quality or disreputable drinking place. ↩︎